After making its worldwide debut at last year’s Kicking + Screening Soccer Film Festival, Soccertown USA was set to take the 2020 festival circuit by storm. Stymied by the coronavirus outbreak, the documentary instead premiered for free on YouTube, and has since racked up the views. We sat down with film co-writers and executive producers Kirk Rudell and Tom McCabe to discuss how one New Jersey town had such an impact on U.S. soccer.

This wasn’t the original plan, but it’s a no-brainer given the times in which we’re living. Kirk Rudell and Tom McCabe wanted to heavily push their documentary Soccertown USA in 2020. The feature-length film won the Player Pass award at the 2019 Kicking + Screening Soccer Film Festival, and they wanted to continue that momentum during this year’s festival circuit. 2020 had other plans.

Rather than shelve the rollout until the COVID-19 crisis died down like many other films have done, Rudell and McCabe — teammates under Bob Bradley at Princeton back in the day — released it for free on YouTube as a gift to the soccer community during these trying times. And we sure are grateful for that.

To make it work, it required some elbow grease, with Rudell narrating the film himself late into the night. It got so rough that he needed to take McCabe’s last cough drops just to get through it. But they decided to do it because it’s a story worth telling and sharing with the masses. It’s a movie by people who love the game, for people who love the game. One that remembers an often forgotten generation of soccer heroes and explores what many consider the birth of modern American soccer. It shows soccer is America’s game as much as anybody else’s, and demonstrates that just because it’s not as popular as other sports here, it doesn’t mean Americans don’t understand or love it.

Soccertown USA shines a light on Kearny, New Jersey and three locals who saved U.S. soccer and turned it into what we see today. In true Tarantino style, the film begins at the 1994 World Cup in the tunnel of the iconic Rose Bowl, right before the U.S. Men’s National Team’s landmark victory over heavily favored Colombia.

The core of that team, Tab Ramos, John Harkes, and Tony Meola, formed years prior in Kearny, America’s first soccer town. Back when the game was on life support and the flame was flickering, the trio met at Thistle United, a newly formed youth club. Rudell and McCabe chronicle the gritty details of their come up, reminding viewers that not too long ago professional players in the U.S. had to carry their own goals onto the field and exist on a five-dollar-a-day per diem.

We sat down with Rudell and McCabe to discuss the making of the film, their favorite moments, and the importance of pickup in the streets.

Urban Pitch: To start off, what are your backgrounds in the film industry and how did the idea of Soccertown USA come to life?

Kirk Rudell: I grew up in New York City and have been out in LA for the last 20 years as a screenwriter. I’ve worked on shows like Spin City, Will and Grace, and American Dad. And I’m also active out here as a soccer parent. My daughter plays club soccer and I helped start an all-girls soccer club out here a few years ago. I’ve known Tom since college when we were classmates and friends, and then teammates. I’ll let him say most of it, but basically Tom was a four-year starter and a real player, and I walked on as his backup for a couple of years as a goalkeeper. We’ve known each other forever, and so when he started working on this idea a few years ago he gave me a holler.

Tom McCabe: I was born and bred in New Jersey, and grew up playing soccer — call it an accidental geography. I grew up in one of these towns in the 1970s that was soccer-first, and that’s when I first ventured into Kearny as an opponent. I remember one day at the Gunnell Oval — the dirt field that gets highlighted in the doc — I’m in one goal and Tony Meola’s in the other goal. So I guess that could be the very beginning of all of this.

I met Kirk in college, and after that I went to teach and coach at a place called St. Benedict’s prep in Newark, New Jersey. That’s where Tab Ramos, Claudio Reyna, and Gregg Berhalter went to high school among others. I really enjoyed that to death for almost 17 years, and along the way I picked up some graduate degrees. I have a PhD in American history, and I now teach at a Rutgers-Newark satellite campus. I get to teach things like history of Newark and the global history of soccer, so I come at this from the historian’s angle.

When the initial interviews for the movie happened, Kirk and I had a fateful discussion at one of the reunions at Princeton, and he was interested. I had enough courage to say, “Hey, can I send it to you?” And that was kind of the beginning of us joining forces. He probably joined halfway in, so really he’s the finisher, right? If you want to push the starter and backup image to its logical conclusion, he was definitely the starter having written in Hollywood and knowing stories so well, and I was definitely the backup and learned so much from him. I had a couple trips out to LA where I was literally sitting at his elbow in his office. We wrote the story and then helped produce it. I learned how to approach this from a TV or documentary angle along the way, which is one of the great gifts of this, as well as a stronger relationship with Kirk.

So Tom came with the facts and Kirk added some spice to it.

Kirk: Exactly. And for me, growing up in Manhattan when I did, club soccer was exotic. We just played high school stuff, and it was harder to find. We played in Central Park or a couple fields by the river on the West Side. It was harder to be passionate about playing the game in the city where I grew up, and what was crazy to me was I had no idea what was happening right across the tunnel from where I was. That it was sort of the heart of American soccer right across the river and it had been there for longer than soccer has been almost anywhere in the world. And that was a revelation to me.

Originally Tom was working on this as a book, and when he decided to make it a documentary, he either called me or emailed me saying “Hey, you’re the closest thing I know to a documentary filmmaker, what do you think of this?” I love story telling and I love soccer. And I also love the immigrant experience. That is always interesting to me.

Is this your first foray into documentary filmmaking?

Kirk: Yes. I’ve been a screenwriter and a playwright for 25 to 30 years almost. I’ve always been a storyteller, and I have friends who do documentaries and have seen their edits and watched their process. So I was familiar with it, but I had never done one myself. There’s an old saying about music and how it’s sort of all the same song. When they would ask Willie Nelson, “How are you a country guy singing these old 50s standards?” He’d say it’s all the same song. I think that’s sort of how I looked at documentaries. It’s all storytelling. And whether you’re writing a movie or a sitcom or a documentary, if the story’s not compelling, if the narrative arc isn’t interesting, if you don’t care about the characters, then people aren’t going to watch.

As a historian, a soccer player, a scholar, and as a guy from New Jersey who knew these guys and grew up in it, Tom brought a breadth of knowledge and understanding to it that I could never have. But then I was able to bring in the sense of storytelling and character, and together we were able to knit this story from that.

Tom, what was it like playing against Meola, Ramos, and Harkes at the time?

Tom: You knew these guys were special. I’m the same age as Tony Meola — Tab and John are a couple of years older, so I didn’t get to play against them, but I knew who they were. At tournaments you would see them and marvel at their skill, particularly Tab. He was one of his kind. As Robert McCourt, his friend and teammate says, he was like a Leo Messi of his time. His ability to dribble and unbalance people and create was just extraordinary. So you knew that these guys were the best in New Jersey and made inroads into the youth national teams. Then they explode onto the full national team right at this moment where they’re going to help the U.S. qualify with more or less a college team for the 1990 World Cup, which was crucial because the U.S. had just been awarded the 1994 World Cup.

So, to qualify for ’90 was super important. This is one of the debates that I have with my soccer historian friends: What’s the most important, meaningful moment in American soccer history? Paul Caligiuri in the movie says 1994. I really think he’s being modest. It’s Paul Caligiuri’s goal in Trinidad and that shutout by Tony Meola. That’s the moment that then creates this trajectory where there was uninterrupted qualifying up until the 2018 World Cup, the staging of one of the best World Cups in history in ’94, the coming of MLS in its wake, and then what we’ve been able to accomplish as a soccer nation since. So, to tell a version of that story through the local lens, through Kearny and New Jersey, it was a storyteller’s dream.

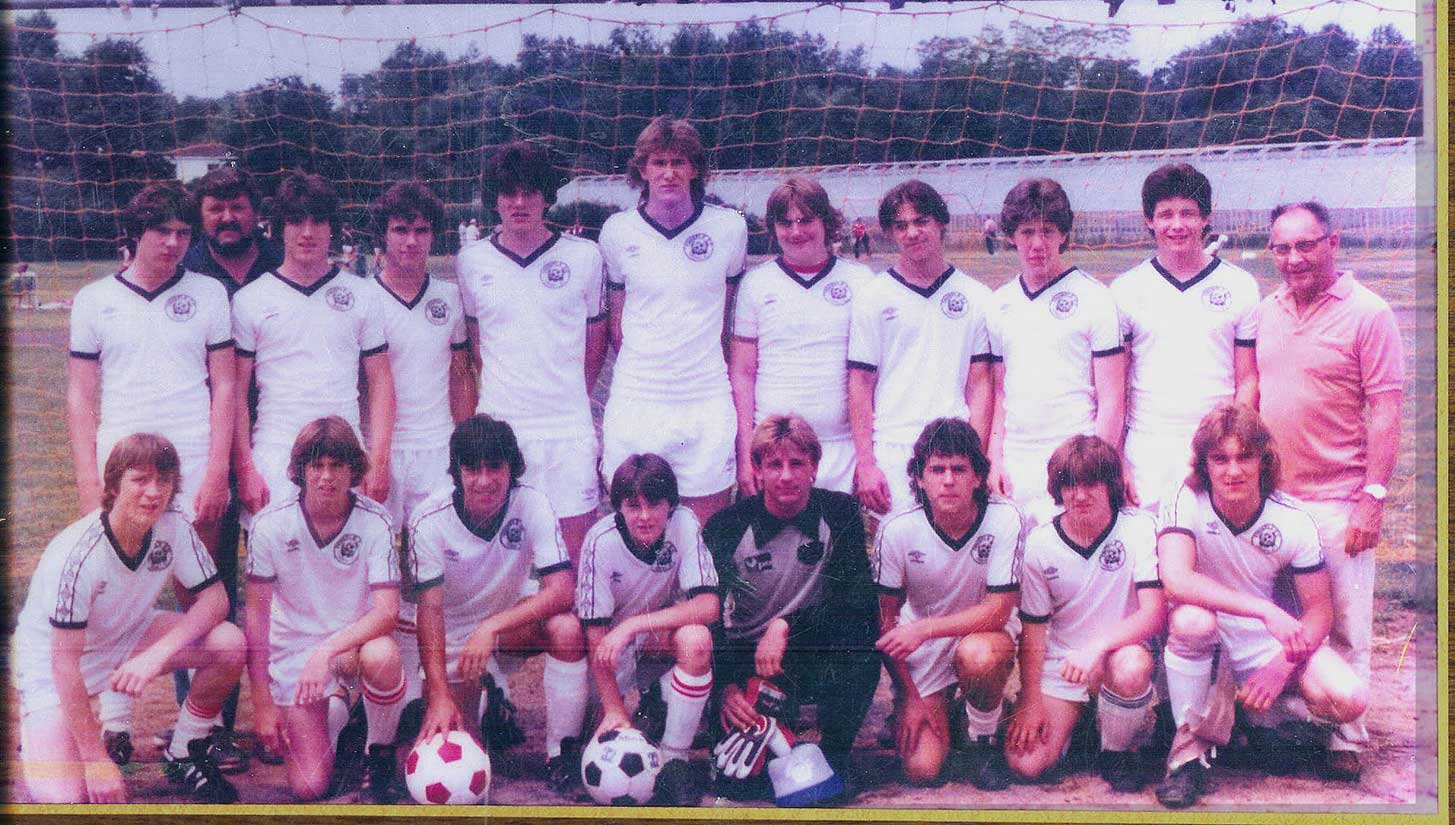

The documentary features a ton of old photos and videos of Thistle and Kearny. Can you elaborate on the process you two went through to dig up all that stuff? Was it an arduous task?

Kirk: That is Tom the historian, that was Indiana Jones.

Tom: Right. So I’ve been working on the project longer than the documentary. Probably going on 10 years trying to tell the story of American soccer through the lens of Kearny. You start at the very beginning with the mills and the Scots coming, and then all the way through these three guys getting to be pioneers in MLS. As I said, I’m from North Jersey and I know a lot of these people, so I started to ask around for who to talk to. And then you’re getting to dining room tables and photo albums come out. The shoe box comes out, or, “Let me go upstairs and get that,” which is the historian’s dream. The classic scene is Mr. Meola saying, “You want to go around in the basement?” And he must’ve had like 200 video tapes of Tony’s games across time. College, youth, national team, MLS, all of that. So, yeah it was digging through the local photo albums, the attics, and the collections.

But I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention one turning point. I was living in Maryland at the time. I get a call from a guy and he says his name’s Kiko Doran — he’d go on to be one of the executive producers. He says, “I hear you’re writing a book on soccer in Kearny. You want to make a movie?”

That jump-started this process and we kind of got a little bit down the road, did some pre-production stuff, interviewed some people, and we realized, woah. We need an VP, and we need someone who can shape this story, so that’s when Kirk comes on board. And then a freelancer in LA, Robert Penzel, who we nicknamed Bobby Wood — that was his soccer name — he comes on board, and then he knows someone who can do the score. So, it was really a lean team that kind of came together. And importantly, two guys from Kearny. Kiko Doran as I just mentioned, and then Chris Garing who came on as a producer as well. So, I think we were smart in getting some of the local gravitas on our team.

Kirk: The community was excited because they wanted their story told, and so people were incredibly generous about their time and their old clippings and tapes. And then Tom also spent some time going through the U.S. Soccer archives and digging up a lot of stuff. He was doing all that leg work with his skeleton crew to try to get all that stuff together. And it was exciting for us every time he would come up with another thing. You can talk about things that happened, but seeing them means so much more.

There’s a portion of the documentary emphasizing the competitiveness that Ramos, Harkes, and Meola learned from playing pickup every day. How important are things like street football to the growth of the sport here?

Tom: This is where all the best players come from, right? These kinds of urban pitches, winner stays on — I want to keep playing so I have to figure out a way with me and four others to stay on. And then those are the building blocks of the game. You can take that skill, that mentality and then bring it to 7v7, 11v11, and all over the world. Whether it’s Glasgow where these guys had roots, or Buenos Aires or Rio or Sao Paolo. I mean, this is what happens all over the world. It was being recreated in this American setting. That was really what gave them their competitive advantage, their drive. They knew when they played for Thistle, Kearny High, or the national team that they could look to each other and know that they’ve been through the battles on that blacktop. We’ve been through the battles on the dirt fields in the swamps of Jersey. And this is just another battle.

Kirk: I think after that Trinidad game when the U.S. got knocked out and there were these convulsions in U.S. Soccer — what’s wrong with us, what do we need to do, how do we fix the pyramid, what’s missing? And there were a few things that kept popping up. People were like, “Kids need to start playing futsal and pickup soccer. We need kids developing a love for the game and individual flair and we need more technical players. And we need to reach kids from underserved communities and lower income areas who can’t afford expensive club fees.” And, again, Tom and I were working on the documentary and we would talk about it and go, “Everything that people are saying is what Kearny was doing for generations.” They already had it, we already know how to develop good players and how to create good soccer. We have been doing it, but that doesn’t make it easy to do, because you need safe places to play.

Fields cost money, coaches cost money, so it’s not that you can just do it overnight, but absolutely getting kids who can’t afford the big suburban clubs and getting them to play pickup, all that stuff is absolutely critical to growing the game and making it stronger here. I think that when you look at how these guys develop, the fact that Tab Ramos could go out there and play with the Brazilians wasn’t an accident. Obviously, he was a brilliant player, but the way he had grown up playing, the way Harkes had grown up playing, allowed them to walk out on that field against those kind of guys and feel like they belonged.

I don’t want to start a fight or be divisive here, but who’s the best player out of Harkes, Meola, and Ramos, and why?

Tom: Tab Ramos, because he just is.

Kirk: This won’t be divisive because I think if you ask those three guys they would say it’s Tab. As great as Harkes was, and as high a level as he played at — goal of the year in Wembley and all that stuff — even he would probably go, “Yeah, but Tab was another level.” In terms of his understanding of the game and his ability to play.

Tom: Yeah, and that’s really interesting. When you throw Tab into that mix in Kearny — which was very much Scottish and Irish — and you throw this Latin American flair, I think it’s a precursor of what we now see in the American soccer community. You’ve got your European roots, you’ve got your South American roots, you’ve got African and Caribbean roots. That’s who we are, and Tab was a harbinger of things to come.

Kirk: But if you ask those guys who is the best athlete, they’d probably say Tony, who was a freak. We wanted to put a little bit of that in. The idea that his senior year Tony was like “My best friend’s my backup keeper. I want to give him some minutes, and I want to have some fun, and I already know I’m going to UVA next year, so I’m going to play forward my senior year and lead New Jersey in scoring.” And then years later, “I’m going to try to be a place kicker for the Jets.” Of the three of them, Tony was probably the prototypical great American athlete who was also just a crazy good keeper.

What’s next for you two? Do you have any other work coming out on the horizon or any more soccer-related content planned?

Tom: I will go first on that because I am in the weeds researching a book on early American soccer. I’m back kind of doing what the historian does. Wrestling with the documents and trying to tease a story out of it. I’m back in the 1870s, ’80s, ’90s, telling the story of the oldest football association outside of Britain, the American Football Association. But, would I love to get back into the documentary game in some fashion and tell another soccer story? Yes. I mean, as Kirk said, we’re storytellers. And I’ve learned a lot from this process and I’ve enjoyed it. And I think anything we — and I’ll say we because I would love to work with Kirk again — take on next, we’ll just take these lessons with us and make the next one even better.

Kirk: Tom and I, we’ve been friends, we’ve been teammates. And it was really fun to be collaborators on this, so if there was another story that we could work on, we would both jump at it. But Tom’s got his scholarship he’s doing, and I’m trying to make more TV shows for your quarantine entertainment, so we’re sort of juggling the day jobs with this. But I think for both of us, soccer is such a passion and such a part of our lives anyway that we are both always looking to make room for another soccer story.

Interview edited for clarity and brevity.

Watch Soccertown USA in its entirety right now on YouTube, and follow the film on Twitter. Photos courtesy of Soccertown USA/Soccertown Media

[…] https://urbanpitch.com/a-conversation-with-kirk-rudell-and-tom-mccabe-co-writers-of-soccertown-usa/ […]