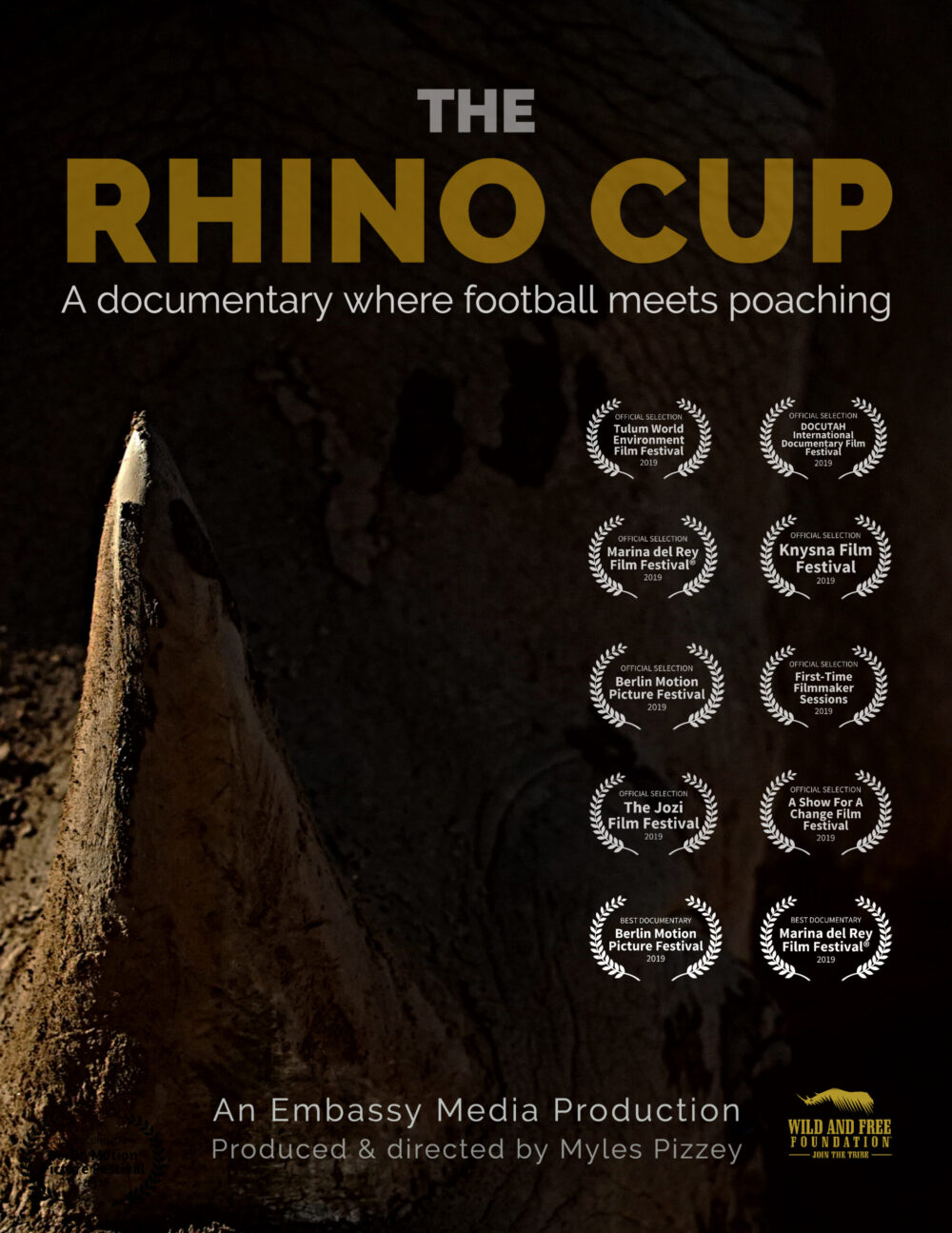

Facilitated by the Wild and Free Foundation as an effort to curb animal poaching and the violence that comes with it, the Rhino Cup Champions League has been an unequivocal success. Documenting the league’s origins, stories, and challenges, The Rhino Cup is a gripping film that showcases the league’s power to unite communities across Southern Mozambique. We spoke to filmmaker and Wild and Free football consultant Miles Pizzey to get more insight into the film and the RCCL itself.

“He decided that shooting at each other wasn’t the way forward, so he started a foundation.”

Filmmaker Myles Pizzey is talking about Matt Bracken. He came across the American when he wanted to make a film about poaching. Having reached out to various organizations, the Pittsburgh’s native’s idea appealed to Pizzey.

“I stumbled across the Wild and Free Foundation and saw they were planning this Rhino Cup,” Pizzey said. “I managed to track down the guy [Bracken] that ran it. We had a chat and agreed to meet in South Africa where I would follow them around and do some filming on their behalf.

“Originally it was to film video content for them, but after seeing the footage I thought it could be something more.”

The “it” that Pizzey is describing is the Rhino Cup Champions League.

Bracken is an American who had trained as an anti-poaching ranger in South Africa. His training gave him an insight into the constant killings between those poaching and those protecting animals across Kruger National Park in South Africa and Mozambique.

Bracken and his colleagues went to the villages in rural Southern Mozambique where they knew poachers lived and simply asked, “What can we do?”

The answer given was “football.”

Pizzey’s film, The Rhino Cup, documents this incredible initiative that continues to benefit all of those concerned. It was the local villagers’ idea, and the Wild and Free Foundation facilitated it.

The goal was to give villagers who may have poached a sense of pride and of purpose. In 2016 the foundation organized a trial tournament in the region of Sabie with six teams, which proved to be successful.

A year later, a full 12-team league was in place, with its own eight-person committee organizing proceedings.

Pizzey traveled from his base in Switzerland, where he had moved to work for UEFA, to Mozambique six times during the making of the film. Not only was he the filmmaker, but he ended up as the foundation’s football consultant as well. Pizzey, from Ascot in the UK, is a big football fan, far more than Bracken and his colleagues.

“I sort of became the football expert if you will,” Pizzey said. “Matt and [Nel] Rohan [Bracken’s partner] barely understand the rules, so I had to talk them through that. I explained what the Champions League is and how it’s different, how leagues work compared to cups.”

This organization, along with some financial support, was what the region needed. One village chief said: “Every village already has a soccer field and the people are knowledgeable and passionate about the game, but there are no uniforms, shoes, or referees. We don’t have a way to transport teams to play each other or maintain the fields.”

It was the village chiefs who provided the understanding in the first place. Pizzey admits that there was some pessimism and reticence to begin with, but in an environment where traditional hierarchies are an important part of life, having the chiefs onboard was crucial.

“The chiefs tend to understand where you’re coming more than the average villager, which is completely understandable,” Pizzey said. “What’s understandable about me turning up with a camera and asking questions?

“The first time I was there was very different to the most recent time because I had to gain their trust. The last time I went I took a projector and showed them the film and they loved it.”

Pizzey is keen to stress his understanding for the poaching that goes on in the region. While he’s completely against it, he points out the dichotomy of some of the poorest people in the world living next door to something so valuable.

Nothing in the film is pre-arranged. There’s a genuine spontaneity and thrill from the people featured — poachers included (something rarely captured on film) — that comes from the ad hoc and sometimes clandestine way in which it had to be filmed. It is an incredible insight into a project that is impossible to call anything other than a success.

This season, the league features 24 teams in addition to a women’s league. In total, 600 players, coaches, and administrators are involved. The foundation pays the committee a salary to run the operations and prize money is awarded to the winners.

Villages who previously saw very little of each other now regularly meet for league fixtures that span an area of roughly 30 square kilometers.

Crucially, poaching is down, as is the number of poachers who have been killed by rangers.

It’s difficult to put numbers on the success as Kruger National Park doesn’t release full figures on rhino numbers for obvious reasons. Local communities, however, say not only has the killing of rhinos and poachers fallen, general crime in the area has too.

In 2019, Kruger National Park said it estimated that during the Rhino Cup Champions League season, 10 rhinos per month were saved along with a 90 percent reduction in the number of deaths and arrests of poachers.

The aim is that the league’s infrastructure will help bring enough money into the region to help set up profitable farming techniques.

It could also help build schools as well as introduce wildlife — much of which was wiped out during the recent civil war — back into the area. Wildlife in Sabie and the surrounding regions could then lead to conservation and tourism.

It’s key to emphasize that this was not just a one-off tournament. It’s the start of something that can be developed and harnessed.

“The plan is to take it to other countries,” Pizzey said. “Other places in the southern basin of Africa — Botswana, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Lesotho, South Africa — could have similar leagues. There could even be a champion of champions tournament, just like our own Champions League.”

For Pizzey, who has been a producer and filmmaker for over 20 years, this particular project has an emotional investment. The league is something he’ll forever be associated with.

“I’ve stayed in touch and made good friends, I even sponsor one of the teams now,” Pizzey said. “I’ll definitely be back to film some more.”

Who can blame him.

The Rhino Cup is available for free preview via Football Shorts until Friday June 19. Pizzey aims to have a full release later this year.

Images via the Wild and Free Foundation.

Fantastic article, thank you Luke. For more on how football can be used as a positive vehicle for change you can learn more here – https://www.wildandfreefoundation.org/

Save a Rhino today by donating to a good cause.