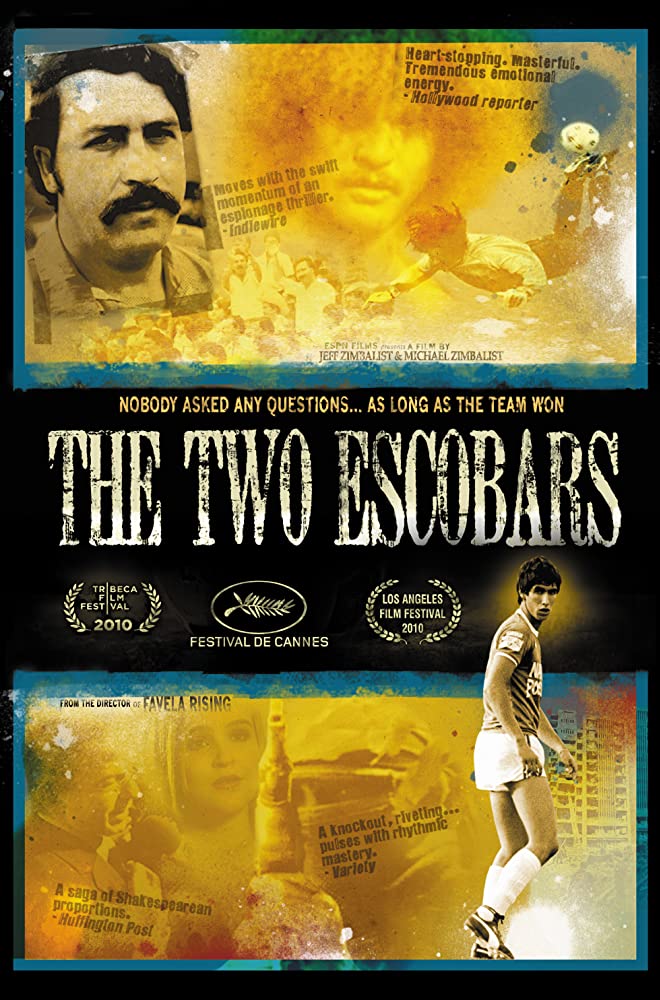

As we near its 10-year anniversary, we revisit the groundbreaking film The Two Escobars, which remains the gold standard for soccer documentaries today. We sat down with director Jeff Zimbalist to discuss the process behind making the highly successful film, and why soccer and storytelling are a powerful combination.

While the collection of soccer-related feature films is a bit lacking compared to other sports, the beautiful game has been a steady force in the world of documentaries. At the center of that universe is The Two Escobars.

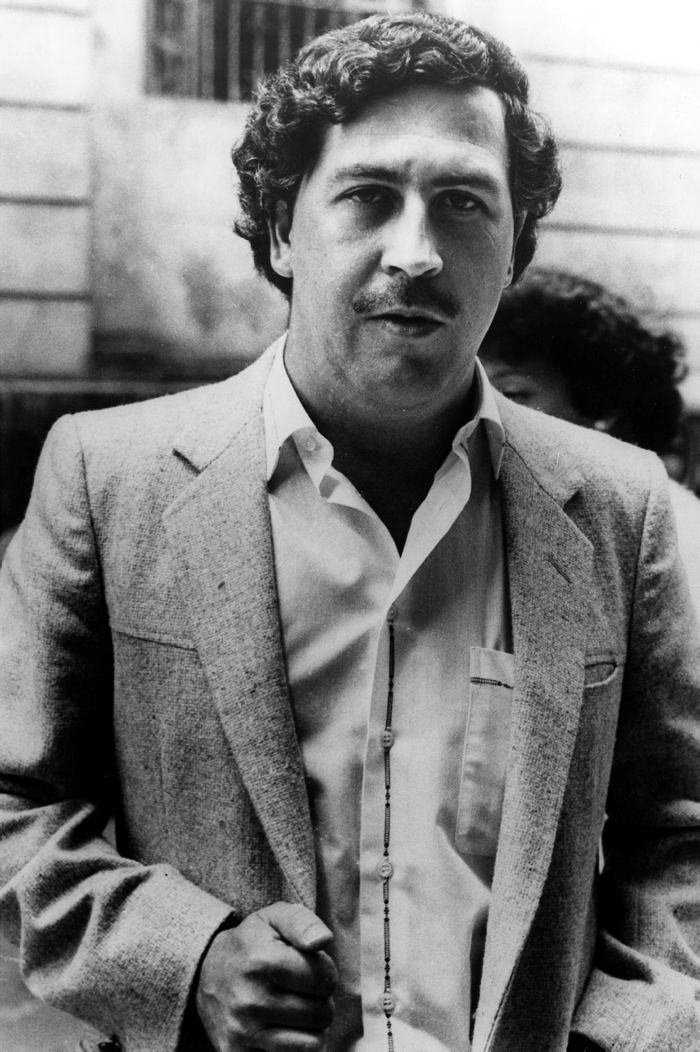

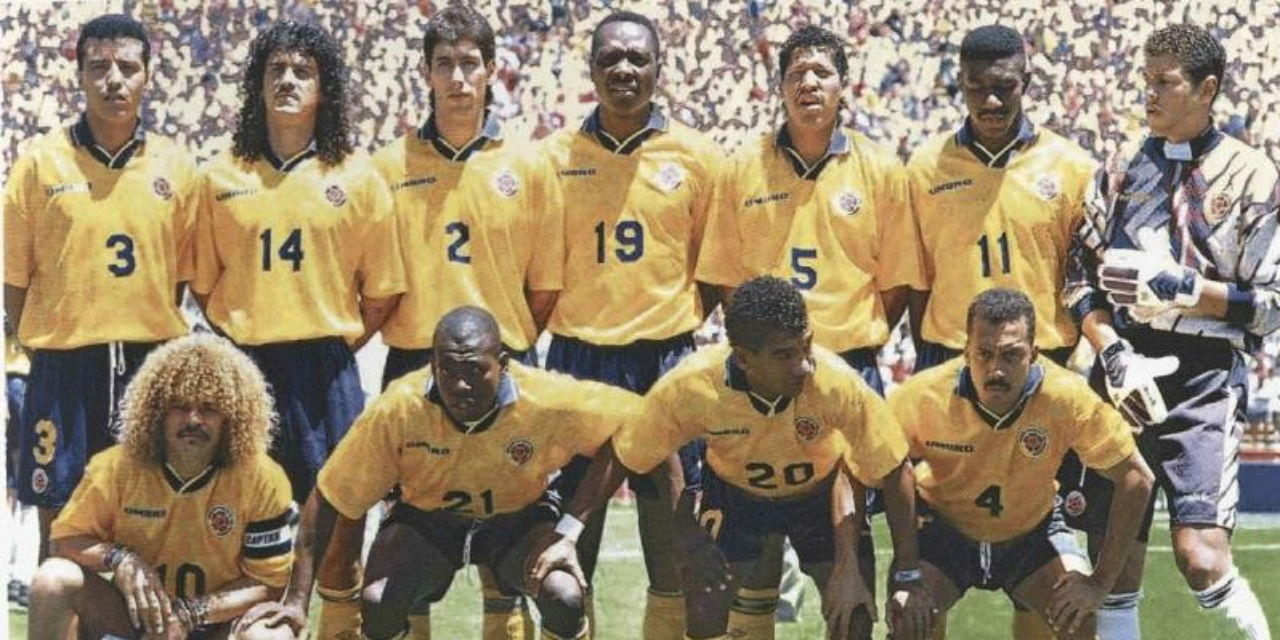

The eponymous characters — Andres, the Colombian national team captain, and Pablo, perhaps the most infamous drug kingpin of all time — are the focus of the gripping and at times heartbreaking film that highlights the dichotomy between soccer and drugs in Colombia leading up to the 1994 World Cup.

Fresh off an embarrassing showing in the tournament and amidst the chaos of a power vacuum caused by Pablo’s death, Andres was murdered in what was reported to be retaliation for his own goal which effectively led to Colombia’s elimination. Though under much different circumstances, Pablo and Andres suffered the same fate, and it’s a little alarming to think that if Pablo hadn’t been killed, Andres probably wouldn’t have been either.

For many people throughout the world, this isn’t out of the realm of possibilities even today, but for the largely American audience of ESPN in 2010 this was unheard of. A gripping investigation led us to a conversation exploring social welfare and what it means for it to be funded by drug money.

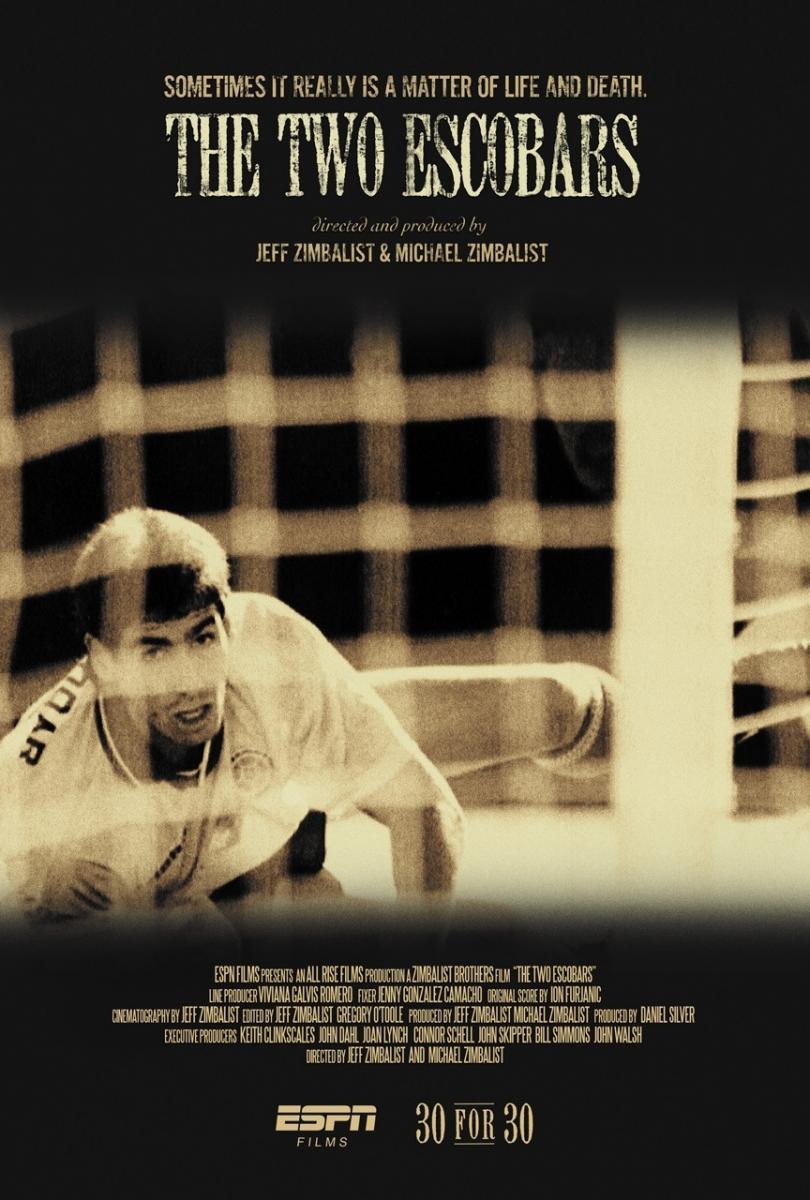

The airing of this film moved soccer forward in the United States. In a twisted sense, the sport became legitimized or at least respected. Getting a national broadcast via the ESPN 30 for 30 series helps, but this film is a blueprint on how to investigate a story. The quality of the craft shines beyond its primetime spotlight.

The Two Escobars ultimately shows us that no matter the topic or even the person, there is always another side, and eventually we need to talk about it.

I was in college when The Two Escobars aired for the first time and I still remember how all of my sports friends who didn’t know soccer now had something to talk about. They were excited to bring it up with me, who they knew to be a fan, and talk about the complexities of those players supporting a drug lord. These were basketball nerds from middle America — the power of documentary is its ability to connect people that would never meet otherwise. My friends were starting to understand the famous Bill Shankly quote, “Some people think football is a matter of life and death. I assure you, it’s much more serious than that.”

The Two Escobars also debuted a few weeks before the 2010 World Cup, an event where people who don’t follow the sport actually tune in, which made for a timely release to get a foothold into the fabric of the American ethos.

Ten years later and a lot has changed. MLS has added 10 teams with another four on the way. The USL has grown to encompass three different divisions and with NISA, independent soccer has a professional league again. Supporters’ groups are louder, prouder, and have grown in ranks. It’s an amazing time to be a soccer fan in the U.S. (Well, maybe not this exact moment as we are in the thick of COVID.)

Because of its importance and being a catalyst for the growth of the game, we felt that The Two Escobar’s 10th anniversary was the perfect time to catch up with director Jeff Zimbalist, who made the film along with his brother Michael. We talked about the process, how they learned about the story, and what makes soccer unique for storytelling.

Urban Pitch: Why was Colombian soccer so unique particularly in 1994?

Jeff Zimbalist: Firstly, the country is coming off of a civil war where Pablo Escobar’s Medellín cartel was violently facing off with the government and the PEPEs. Every one of those football players is inextricably tied into a set of high stakes life or death choices that exist because of the state of the country at that time. The concept of sport and the stadium as diversion and an escape from whatever madness exists outside of its walls doesn’t apply. Narco football is an extension of society, a mirror of society.

Also at this time, the president Cesar Gaviria launched an international PR campaign to redefine the country’s image by using the 1994 Colombian national team, and particularly Andres Escobar, as the poster boy. So in many ways, sport carried the weight of determining the global perception of a country and the national identity of its population.

Not many films provide positive stories around Pablo Escobar. How do you walk the line of exploring the positive impact of a notorious drug lord?

We did a lot of focus grouping to get that balance right. Part of what was working to our advantage was that it was 2008, 2009 when we were in production on the film, and we were talking about 1994, roughly 15 years in the past.

So there was an opportunity for people to start looking at that time period in their lives with a wider lens, a more bird’s eye view perspective, and reflect upon it as a whole. It’s such a traumatic time in everyone’s life in Colombia. The fact that there were so many opposing points of view from one interview to the next meant that we felt we had a responsibility to be as persuasive as possible for both sides.

The vision was to have the audience’s allegiance and sympathy shift throughout the film, maybe you’re rooting for and sympathizing with one point of view for 10 or 15 minutes and then for the other over the next 10 or 15 minutes. We wanted that sort of tug of war, that push and pull about whether this man was a savior and a saint or a sociopath and a maniac. And also whether football as an institution was suited for such a grand societal responsibility.

Do you think 15 years was enough time?

Even 15 years later, there was danger and stigma. It was such a divisive topic. We were told by Colombians that the country hadn’t had its catharsis yet about the events of that time. In particular, it still was a nation divided into two camps, and for that reason, it was often just still not spoken about.

In addition to the literal bombs, Pablo Escobar dropped a figurative bomb on the society and divided it into these two factions. On one hand you had those who felt that he was an angel, an architect of a better future for the poor, dispossessed, and under resourced. The more we asked, the more anecdotes they would each come up with — ways in which Pablo directly or indirectly contributed to health services, security services, recreational opportunities, housing, food and all of these survival resources that the population felt the government had never really provided.

And then the other half of society saw him as this sociopathic mass murderer, who not only waged a war that cost many thousands of lives, but also was ruthlessly breaking the law left, right, and center. He was destabilizing every aspect of Colombian society and was responsible for a portrayal of the country as a hotbed of criminals and corruption to the rest of the world. We know the truth was that over 90 percent of the population were peace-loving, hard-working people, but that’s not how they were perceived during those times.

How did you find out about the story?

We had a friend at the time who was a soccer fanatic, Nick Sprague, who initially mentioned the idea of doing an investigation into the murder of Andres Escobar. What were the circumstances that led up to that? We were hoping at the onset that it was more than just an examination into who pulled the trigger.

We wanted it to branch out and start to become a lens through which we could understand what was going on in Colombia at that time. Early on in the process and talking to ESPN, it was really just a hypothesis that we would be able to connect the two Escobars. We knew that both had an enormous amount of impact on Colombia during the same time period, and we knew that they had intersected to a certain extent through the sport, but everything else was revealed through the journalistic process.

Ultimately, what we found is that they represented these two sides of Colombia, and that their interactions with each other as the film outlines, stand in for this microcosm, for this symbol of the ways that those two camps in Colombia viewed themselves and each other. We did learn in our process that, had Pablo not died, it was very unlikely that there would have been a state of chaos and a race to the top in the criminal underworld that would have allowed for a soccer player to be murdered for a mistake he made on a playing field. Essentially, had Pablo not been killed, Andres probably would not have been either.

Was ESPN open to this kind of story from the beginning?

The initial order from ESPN was a one-hour broadcast slot. And it was already a risk. This was the first season of the 30 for 30 series. ESPN had not traditionally been a powerhouse in the independent documentary space, so they were already taking a risk with the format. And then on top of that they’re choosing to make one of their first season films about the sport that Americans are least interested in, particularly back then. And then thirdly, to make a film that’s almost exclusively in Spanish and subtitled for primetime broadcast is a trailblazing choice.

We came to them and said that we wanted to expand it to be a feature-length film, and that it was not only going to be about the world cup and Andres, but also we wanted to essentially tell a history of Colombian politics and crime during that era, which could arguably have just been cast off by a sports network as not who their audience is. Instead, they embraced us and allowed us to double the duration of the film. So we can attribute a lot of the film’s success to Connor Schell and Bill Simmons and the 30 for 30 team at ESPN. They allowed us to expand the project and the scope of the investigation and broadcast it primetime, fully subtitled, in a two-hour time slot.

With no production to do, how did the editing process work?

With The Two Escobars we had lived and worked in Colombia, in Medellín primarily. We’d done some other projects in Colombia prior to this film, and our experience of living and working amongst the Colombian population was an overwhelmingly positive one. So much so that my brother fell in love with the country and bought a condo in Medellín and spends as much time as he can there even to this day.

The film’s launching point was an investigation into the murder of an athlete and what that told us about the phenomenon called narco fútbol, and in turn, what narco fútbol told us about Colombia during a time of war and conflict. But it was also important to us that we not just propagate the negative stereotypes of Colombia as sort of a hotbed of violence, drugs, and corruption. We really made sure that we were extending the storytelling to include our direct experience of Colombia, to portray it also as a place that’s coming together and overcoming these types of adversities from poverty, violence, corruption, racism, classism, etcetera. So, particularly towards the end of The Two Escobars, we made an effort to push a different perception of the country and the people.

Soccer is a subject or theme in a lot of your work, how did that come to be?

We were always interested in primarily using sport as a vehicle to talk about society and culture, as opposed to staying within the container of the sport and its fan world. I don’t think anybody would take issue with the generalization that football is the sport with the deepest relationship with and impact on society and culture historically.

We have done other sports stories, we’ve also done music stories, we’ve done crime stories, but our criteria tends to be: How is this universal? And how is this deepening our understanding of human behavior in general?

We really do view sport, music, crime, or any of these genres, not just as mirrors and reflections of society and communities gone wrong, but also to focus on their potential to unite people and build solutions across combative populations or in particularly confrontational situations.

The idea of sport and crime is often attributed to films like The Two Escobars and some of the other work that we’ve done. But we are also equally excited about and inspired by the stories of sport and resolution or sport and unity.

We’ve made a number of non-crime soccer films now, as well — Nossa Chappe: Our Team, which is a story of how different people handle tragedy and come together to heal, to Pelé: Birth of a Legend, which is a scripted studio feature about national pride and the empowerment of the underclass. We’ve done more competition format projects like Phenoms, which is tracking the careers of young stars as they move up in the ranks through the Premier League into their national teams, or something like Cantera 5v5, which is a new series we just released on ESPN, NBC Universo, and Telemundo.

The question we ask ourselves at the onset of all of these projects is, how does the play on the pitch directly impact the events off the pitch and vice versa? Soccer is not only loved by the most diverse range of genders, classes, and nationalities across the world, but also it really is an extension of what’s happening in the offices, streets, and homes of society at any given time.

Interview edited for clarity and brevity.

[…] https://urbanpitch.com/two-escobars-jeff-zimbalist/ […]