From designing the official MLS Black Lives Matter t-shirt to creating his own brand, Warren Creavalle refuses to be confined to the boundaries of a traditional athlete. We sit down with the MLS veteran to discuss the process behind the tees, his work with the MLS Black Players for Change coalition, and the overall reception of his designs.

During last summer’s MLS Is Back tournament in Orlando, you might have noticed some super slick looking Black Lives Matter t-shirts worn by the players and coaches of all teams. Black shirts with bold yellow lettering on the front and an intricately detailed design on the back. This wasn’t a coordinated design by a team of expert consultants from MLS super-sponsor adidas, instead it was from Warren Creavalle, then a player with the Philadelphia Union.

While Creavalle’s time with the Union might’ve recently come to an end, in five-plus years he left a lasting impact on the club and community. He earned the respect of fans, teammates, and coaches alike, evident in the heartfelt tributes to him after the Union declined his contract option following the 2020 season.

Not every player gets these heartfelt goodbyes when their time comes to an end so it’s a testament to the way Creavalle played and carried himself with the club. While Creavalle is one foot in and one foot out of the league at this point, he’s still got plenty to look forward to. For one, he’s expecting the birth of his first child, and additionally his creative brand Creavalle already boasts a series of impressive releases, and with more time spent there who knows where he could take it.

I was able to speak to Creavalle on the phone to get the low-down on the BLM t-shirts, how they were able to garner nationwide coverage, and what it was like working with both the league and the MLS Black Players for Change at the same time.

Urban Pitch: Thanks so much for taking time to talk with us! First off, how did you feel about last year with the Union and winning the Supporters Shield?

Warren Creavalle: I think the Supporters Shield is getting more and more respect within American soccer. With American sports, in general, it’s all about the playoffs, so with that it kind of takes away from what is viewed in other leagues as the normal championship. Overall, there were a lot of positives even aside from that. I think our club was a leader in the social justice movement. We had a lot of people in our locker room speaking up and being active in their role and in how we wanted to represent ourselves and represent the club. That was cool. Anytime you have those kind of positives within the year we just had you have to take those as a win.

The Philadelphia Union’s jerseys are honoring the names of members of the Black community who lost their lives to police brutality. pic.twitter.com/NWQZrlgvpq

— ESPN (@espn) July 9, 2020

In what ways did the club support the movement for social justice?

There were definitely a few other clubs that really controlled the narrative and were on the forefront of the movement as well, so I don’t want to take away from any of the other clubs. But I think that ours in particular, the individuals in the locker room, with myself, Ray Gattis, Mark McKenzie, our captain Alejandro Bedoya, we had a really vocal and outspoken group, and in addition to that we had an ownership group and coaching staff that was really supportive of everything we wanted to do.

We had plans to make a statement in our return to play down in Orlando and it was something that had to be kept under wraps. It was against the rules, as far as the jerseys go for the league, so there was potential we would have backlash, but it was a statement that we wanted to make. And it was supported by the coaches, it was supported by our sporting director, and our ownership, all the way from top to bottom, even down to our kit guys who had to make those jerseys for us. So things like that are really telling about the organization and what they stand for.

Can you go into detail about the statement you made and how you pulled it off?

We played in jerseys with the names of victims of police brutality on the back. It was our first game in Orlando. The timing was kind of crazy. The first game in Orlando was Miami vs. Orlando and Black Players for Change, we had our demonstration on the field prior to the game and that was obviously a big moment.

And then for our team we had the first game the following day where the shirts I designed, the BLM shirts, were being debuted and that was the first look at that. It was the warm up shirt so both teams were warming up in that and as we were coming to take off the shirts to start the game, that’s where we revealed the different names on the backs of our jerseys, so it was kind of a build up that came out of nowhere because really nobody knew about it and that was a special moment.

Did it get the coverage you were looking for?

As far as coverage, yeah, it was picked up and it was probably the most press the club has gotten, you know? As far as globally because we had, I don’t want to say an advantage, but we were one of the first leagues to come back and to have that display. And it caught everybody off guard, the commentator was stumbling over his words trying to figure out what was going on and realizing that those weren’t the names of our players on the back of their jerseys.

View this post on Instagram

How did this demonstration idea come about and get organized?

It started with going to work for the Black Players for Change. The organization was having frequent meetings, it might’ve been daily at that point leading up to Orlando. And we were deciding how we wanted to make a stand and how we wanted to show our support, show our protest, and convey our message, and one of the ways was shirts.

So I did shirts with three different messages and sent them out to the group and that was worn by all the Black players and even Black staff members — Thierry Henry and his whole staff, Robin Fraser, I believe Danny Hoesen was there as well, Ali Curtis. That was a cool moment. But taking a step back that was just for the Black players, and then in conversations with the league, they reached out to our group to collaborate to have an inclusive show of support, and I had already worked on the shirts and my teammate Ray Gaddis threw my hat in the ring and said, “Hey, why don’t you let Warren design something?”

So that’s how those conversations got started. Everything started moving kind of quick. I had a couple meetings with MLS and what they had thought about doing in collaboration with adidas, obviously because they’re our outfitter for the league, and the type of messaging they were thinking about doing. So I was kind of the middle man between the BPC and the league/adidas as far as what we wanted our inclusive messaging to be and what we wanted to look like. After we worked out the theme that we wanted to get across, both sides just gave me the freedom to create what that would look and feel like. I’m just glad it was well received.

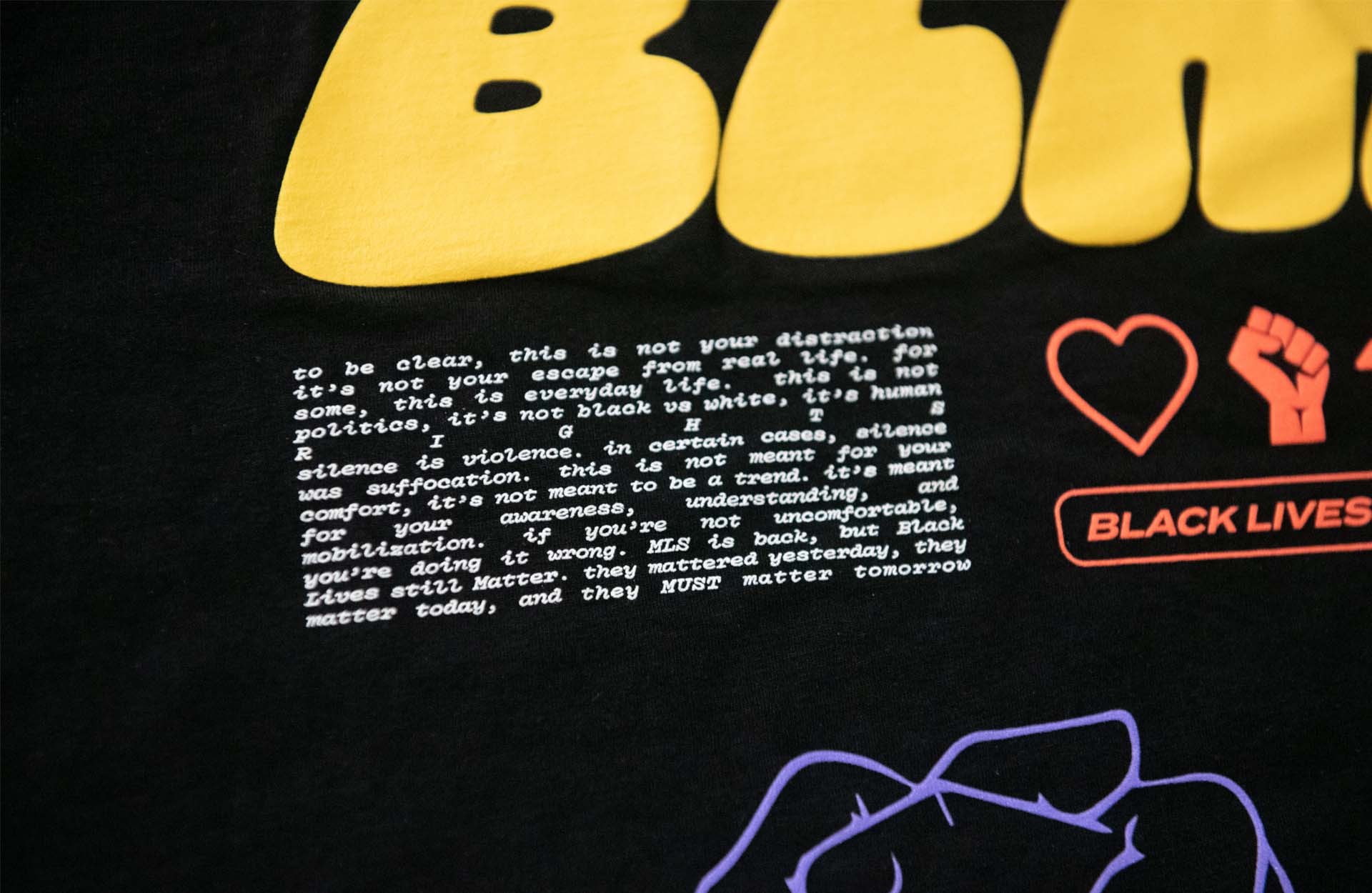

Where did the text come from on the back of the shirt? Who wrote that?

I wrote that as well. A lot of that stems from wanting to be proactive and the cliché narrative that you hear, that people are averse to athletes speaking up. And also Jeremy Ebobisse wrote an article for Medium — he really has a way with words, and can articulate his points in ways that few people can do, just a really intelligent brother. It goes back to that article and addressing what he was addressing, talking about how this shouldn’t be a comfortable moment for you. I kind of took his words and reflected on that and kind of added that to that paragraph as well.

In your words, what does the Black Players for Change organization represent?

BPC is a Black player-driven organization that aims to bring equality and change both on and off the field. There’s different test points as far as what that looks like. It’s programming in the community, it’s Black executives in and around soccer, equality in wages, or just the perception of the Black athlete not being referred to as just fast and strong. Shifting the narrative to appreciate the intellectual side, the knowledge of the game, more than just the physical traits. Giving back to the community obviously. Enabling players that look like us, disenfranchised kids, getting them access to the game. Even the program we’ve already started with new pitches, those are going in neighborhoods that may not have access to the game.

What was the nature of those BPC conversations when they first began?

It was a range of emotions just depending on the day because obviously it was in response to something that affected all of us on a really deep level. So honestly it started as a sounding board, it wasn’t even for a demonstration. “You’re in a similar position to me, like, how you holding up? I’m pissed. You know, we need to do something. And the statements that MLS is putting out is making me even more upset. The Instagram post from my white friend saying I hear you, I feel you, is not enough.”

That’s where it started and it graduated as we started to think and plan, and clearly that was the benefit of that. Being able to talk things out with people who were in a similar situation to yourself.

Were you successful in raising awareness like you’d hoped?

Definitely I look at it as a net positive. I don’t look at it as there’s been this change that we’ve been waiting for for decades. There’s no switch that can be flipped. I think the groundwork there has been really positive as a nation. There was a bit of a shift — there were some alarm bells that went off for certain people and corporations that hadn’t necessarily gone off before and obviously that’s positive. There was a tipping point that reached and it may have had something to do with being in quarantine and enough is enough but we’re still very much in it you know.

What was it like working with MLS on this?

They were definitely helping facilitate it. I think they definitely realized the value in what we were trying to do there and the optics were in their favor if they supported us. There were a couple sly moves on their end, like taking away the national anthem, so there was no national anthem, there was just a kneel on the first whistle. For the most part I think they were genuinely looking for ways to further educate themselves, see what they were doing wrong, and see how they could grow and get better.

We had a ton of meetings with them on that. Different departments, the communications department, and speaking with them and the back and forth with the league office, but even that in itself came after speaking with the group and just Black friends. It was a microcosm of Black people having conversations with white people across America. It’s like fuck — I’m exhausted from even trying to explain it, right?

So you can kind of turn to that, like these are the type of meetings that you’re paying people for, as far as consultation on different topics, but it looks different because we’re talking about race right now. Not that we started this to get a paycheck or a black consultation firm or nothing like that, but I think it kind of showcased some of the other problems in my opinion. Like during the whole design process that wasn’t something that we were paid for, that I was compensated for, and to be clear that wasn’t the reason we were doing any of it, but I think that kind of highlights those things a bit. We were putting this work in for free for a corporation.

Who all did you work with to make the shirts?

I did get the chance to work with some really cool people in the league on pushing that through to the finish line. They were cool with us being able to offer it on the Creavalle site so if nothing else we were getting some cross promotion from it. Getting more eyeballs to the projects that we were doing, I was appreciative of that for sure. Especially working with the nonprofits that we were donating all of the proceeds to, it was a crash course in how things work on the corporate level and especially these nonprofits too.

As far as the collaboration for the design, the league showed me what they were thinking about and we changed it — I think they were going to go with a different message on the front of the shirt and we wanted it to say Black Lives Matter and basically I was like, “Yo, let me do my thing on the back.” And that was that.

With all of these projects and conversations on top of the games, what was the bubble like for you?

For me, when I was done training and done with games I was working on pushing through everything else, to have the shirts available for wide consumption, so I wasn’t really bored down there. There wasn’t a whole lot of excitement, it was, go to training and come back and chill out. I will say especially at the beginning it was kind of weird because it was such an interesting time as far as the virus and you’re seeing people you haven’t seen in forever. I have a lot of friends around the league and I’m seeing them from afar and not knowing whether you can dap up your boys. But once we got over that it was really cool to hang out with old teammates and grab coffee with the homies and chill out and talk about all the bullshit going on.

Any cool things come from the shirt you weren’t expecting?

Seeing the shirt transcend into other leagues was pretty cool. I saw Jason Hayward with it on, Jaylen Brown. Also seeing Thierry rocking it, that was really dope to see. It was captured beautifully by a photographer friend of mine. It was so clean.

We got to do a commercial in collaboration with the NBA guys where we were wearing the shirts that Russell Westbrook created and they were wearing the ones that I created for our demonstration so that was a cool moment as well.

It definitely put our brand and what we do on the radar for people who wouldn’t necessarily have seen it.

Interview edited for clarity and brevity.

Keep up with Warren Creavalle by following him on Instagram and Twitter, and be sure to check out his Creavalle projects on the brand’s official website.

More of this!

Thanks for reading! And will do