With the firing of Jesse Marsch from RB Leipzig there is not one marquee American managing a top team in Europe. The question still remains, when will the U.S. produce a game changing soccer coach?

Pep Guardiola, Marcelo Bielsa, Joachim Löw, Diego Simeone, and Vicente del Bosque are all coaches that in their own way changed the game. Their styles on how to field and coach a team has left huge lessons and building blocks for many future coaches all over the world. And while the United States may not have that international signature manager yet, it certainly isn’t out of the question that we’ll eventually get one. As soccer in the U.S. improves at the player level, so too will it improve at the coaching level.

In a fanbase and program not familiar with patience, it might be hard for USMNT or U.S. Soccer fans to swallow that the U.S. has yet to produce a coach of global respect. Jesse Marsch is not a bad coach, in fact he will most likely go on to do great things, maybe in Europe, but his time at RB Leipzig is a stern reminder that soccer is a unique sport. Marsch, who had been in the Red Bull family since 2015, paid his dues, but when he got the corporation’s top managing job at Leipzig, patience was not in their vocabulary.

Why Marsch was fired is pretty clear. RB Leipzig — who in just over a decade of existence can claim to be the third-most important team in Germany — failed to make it out of their Champions League group, sat in 11th place in the Bundesliga, and were more than likely out of next season’s Champions League altogether. The high press style that Marsch was implementing was abandoned and the brass pulled the plug. Major European soccer clubs can forgive many things, but failing to qualify for the Champions League isn’t one of them. In only 21 matches across all competitions, Marsch produced an 8-9-4 record, and that was all she wrote.

In a sports world where the U.S. is tolerant of “rebuilding years,” the big money of European cup competition is too valuable for teams like RB Leipzig to leave on the table. The culture of top-class European soccer is much more cutthroat. One only needs to look at the NFL, where no matter how poorly teams do, the massive amounts of money they get is almost a given.

Urban Meyer was one of the NFL’s highest paid coaches in his first year out of the college game, but he had an embarrassing run in the big leagues at the helm of the Jacksonville Jaguars. Despite a pitiful 2-11 record, it was ultimately Meyer’s poor relationships with his players and coaching staff that ended his reign in North Florida.

Marsch, whose problems stemmed mostly from tactical issues, seemed to have the allegiance of his players and was a hard worker. But in the end that didn’t matter.

Who is the American Coach to Look Up To?

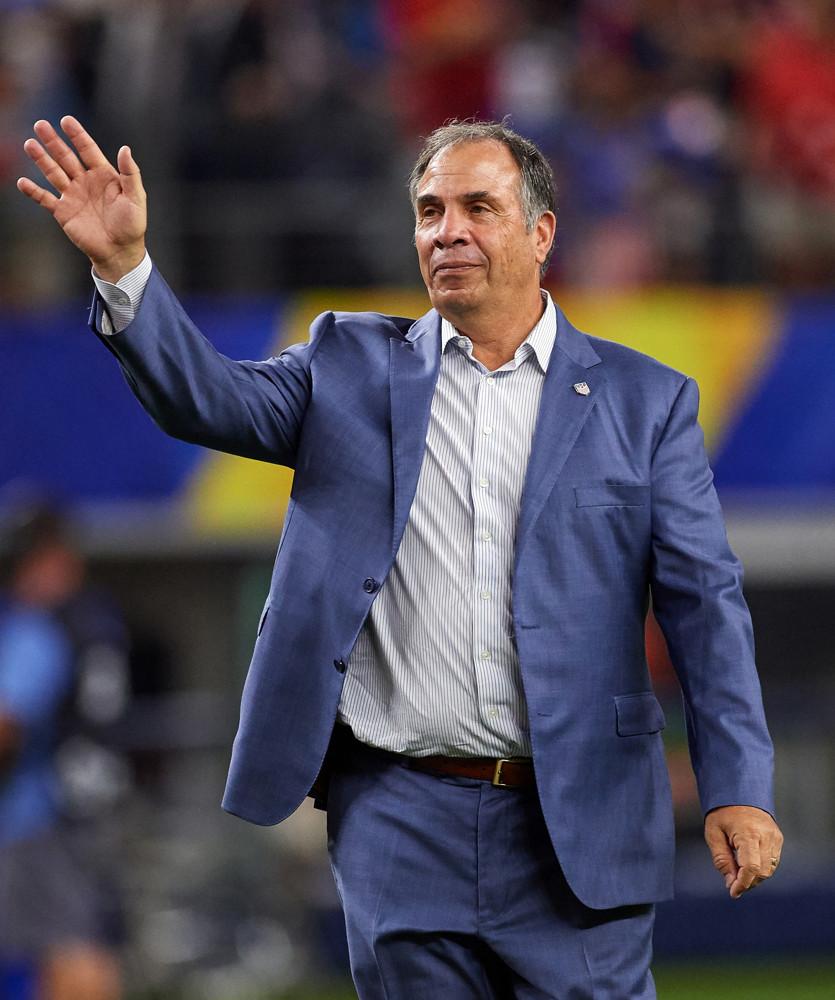

Bruce Arena could and should be the holy grail of American coaches, but even still, his record is too American. A master coach of MLS and still arguably the best coach the USMNT has ever had, Arena’s five MLS Cups were won with a style of play that is seldom used at the top ranks of European soccer.

Arena, an expert in the triangle formation, won titles with Marco Etcheverry, Jaime Moreno, and Raul Diaz Arce at DC United, and later with David Beckham, Robbie Keane, and Landon Donovan with the LA Galaxy. At New England, the triangle style is still paying dividends as Carles Gil, Gustavo Bou, and Adam Buksa make up the new pattern and produced the best regular season record in MLS history.

Today, the game is played much more down the wings, and with at least five critical players in the attack. Bob Bradley, a disciple of Arena, did take the plunge to Europe, but at modest stops in France, Norway, and a woeful spell at Swansea City. Bradley is a bit more modern and much more hands on than Arena. He is a huge student of the game who at times plays a counter attacking style that best showed itself with the USMNT.

Then there is current USMNT coach Gregg Berhalter, the man who is trying to change the way the game is played at the national team level. Berhalter, who assumed control of the national team with modest credentials as a coach, but with great experience as a player, tries to employ a much more fluid and attacking style to his game.

Prone to shooting himself in the foot, Berhalter does know how to adjust, and at the moment he has a 31-7-6 record with the U.S. Though his record and two continental championships are impressive, Berhalter’s true test will come at next year’s World Cup. His disorganized attacking style has yet to pay ultimate dividends on a team that lacks experience at every level no matter how much Christian Pulisic, only 23, plays for Chelsea.

Creating a Coaching Tree

In Argentina, soccer has two languages, both of which are still defined by the coaches that won the country their two World Cups: César Luis Menotti and Carlos Salvador Bilardo. Menotti is a coach known for freestyle play, while Bilardo is known for organization, a 3-5-2 system, and tight style. Menotti went on to inspire Bielsa and Marcelo Gallardo. Guardiola, who was inspired by Bielsa, can also be traced back to Menotti. Bilardo inspired coaches like Diego Maradona, Óscar Ruggeri, and some aspects of his game can be seen by Simeone’s teams.

Tradition plays a key role in defining a style and philosophy of a country and the players it produces. Löw took the German national team to the next level, changing much of the previous style to a more modern 4-3-3.

In the U.S., we are still searching for that style, still searching for that coach that will impose their philosophy and shape the game to come for generations. Much like our current group of players have broken down the walls of playing for the top teams in the world, our coaches will break through in time. It might be messy, but it will happen. As our players become fine-tuned so will our coaches. For now don’t write off Marsch, who may not change the style of American soccer, but could still leave an important mark.