With the Roman Abramovich era at Chelsea all but over, we look back at the owner’s impact — both positive and negative — on the world of football.

On March 2, Roman Abramovich, the owner of Chelsea Football Club for nearly two decades, matter-of-factly announced that he was putting the team up for sale via a statement on the club’s website. Had the announcement come two weeks prior, the message — content and tone — would have come as a total shock.

Of course, that would’ve been prior to Vladimir Putin commanding Russian forces to invade Ukraine. Thus, the Western world hadn’t yet begun to scrutinize its relationships with the prominent Russian businessmen who rose to power and unfathomable wealth in the post-Soviet privatization of Russian state assets. For the past quarter century, a cadre of billionaires and centi-millionaires took to the world’s glamour cities — London chief among them — snapping up prime real estate and marquee assets.

In light of the Ukraine invasion, London has quickly become a far less amenable financial parking lot, particularly for those with close ties to the Kremlin. An initial wave of sanctions by British authorities against wealthy Russians living in London missed Abramovich, though his was one of 35 names on Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny’s list of individuals who should be considered for sanctions.

With the heat ratcheting up in London and the Ruble losing over 40% of its value in the past month, Russian-owned high-end real estate, fine art, mega-yachts and, yes, the odd sports team, has hit the market, with owners looking to cash out quickly. Abramovich was not alone nor, as it turns out, mistaken. Despite saying in his statement that the “sale of the Club will not be fast-tracked but will follow due process,” Abramovich gave interested parties all of three days to submit their £3 billion-plus bids. Fortune was always going favor the decisive here.

As it turns out, the hammer was already dropping. On March 10, Abramovich was one of seven Russian oligarchs sanctioned by the UK for:

- “Having received preferential treatment and concessions from the Kremlin,” (dare I say, duh); and

- Business links revealing involvement in “destabilizing” and “undermining and threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty, and independence” of Ukraine (Evraz PLC, a steel company in which Abramovich had a significant stake and influence, apparently supplied steel to the Russian military for the production of tanks).

With these sanctions, Abramovich’s sale of Chelsea was frozen, along with just about every business aspect of the club.

Abramovich: Origins

By the time most United States-based fans discovered a love for or had regular access to the Premier League, Chelsea was already a trophy-winning perennial power. In a sport full of Manchester Uniteds, Liverpools, Real Madrids, Barcelonas, and Juventuses (Juventi?), it was easy to assume that this was just how it had always been. Not so fast! We should take a moment to discuss what Chelsea actually was prior to 2003.

The first half-century of Chelsea’s existence (after its 1905 founding) yielded precisely zero trophies. After winning the First Division (now Premier League) in 1955, the club did not win a top tier league title again until 2004. During that span, they actually won the Second Division twice, were relegated six times, and faced complete financial ruin in the early 1980s. There were three FA Cups (1970, 1997, 2000), two league cups (1965 and 1998), a Cup Winners’ Cup (1970), and a UEFA Super Cup (1998), but Chelsea was neither a fabled institution nor a fixture in the top tier of the sport.

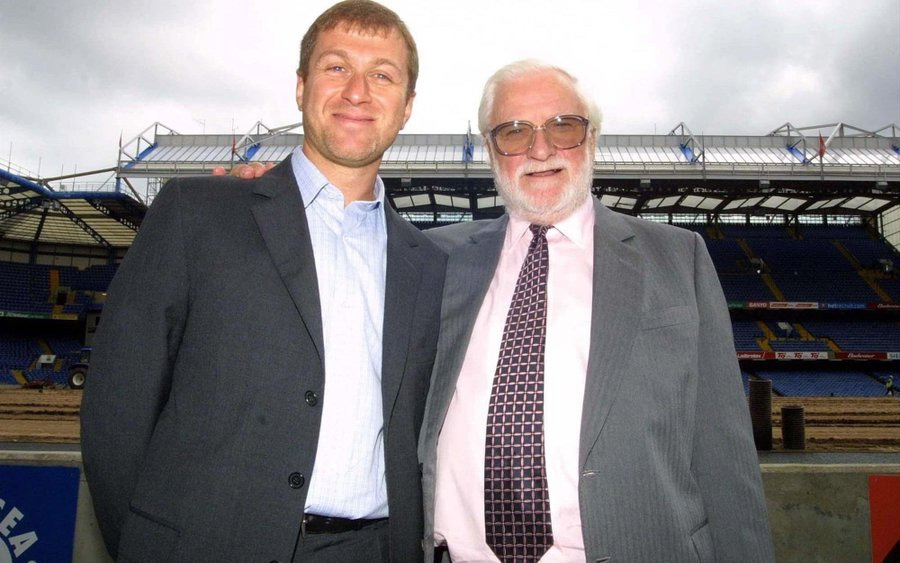

In July 2003, Abramovich, then just shy of his 37th birthday, bought a 51% stake in Chelsea Village, the publicly-traded parent company of Chelsea FC, from a consortium of companies headed by former chairman Ken Bates’ Mayflower Securities, for £29.6 million plus the assumption of the club’s debts. The deal valued the club at £140 million. Under English law, by acquiring a stake greater than 50%, Abramovich was obligated to make an offer for the remaining shares. Over the next few weeks, he acquired shares held by the estate of former Chelsea director Matthew Harding (21%), British media company Sky (9.9%), and other small shareholders, and took the club private on August 22, 2003.

Though Abramovich’s money was more than welcome, there were questions and skepticism — again, with reason — about the origins of that wealth and, well, Abramovich himself. At the time of the Chelsea deal, Abramovich, a confidant of Putin as well as former Russian president Boris Yeltsin, was halfway through an eight-year term as governor of Russia’s easternmost okrug (legislative constituency), Chukotka, where he owned significant mining assets. He was/is one of 23 individuals who acquired former Soviet state-owned assets for pennies on the dollar after the fall of the Soviet Union. He owned 70% of Russia’s fourth-largest oil company Sibneft (since acquired by Gazprom), 26% of Russia’s national airline, Aeroflot, 50% of the world’s No. 2 aluminum producer, RusAl, as well as Russia’s second largest automaker, a metal combine, a bank, an insurance company, a hydroelectric plant, and a pulp and paper plant.

If only anyone had seen the signs. Anyway…

No One Knew What Was Coming

Upon completing his purchase of the club, Abramovich went to work in a way few in England ever seen before:

- That first summer alone, he shelled out over £120 million on, basically, a new squad of players;

- The following summer, it was £92 million more to bring in (among others) Petr Cech, Arjen Robben, and Didier Drogba;

- Two years later, it was almost £70 million more, highlighted by a then-British record £30 million for striker Andriy Shevchenko;

- After a relatively subdued couple of years (“just” £75 million combined), ahead of 2010-11, it was £90 million on Ramires, David Luiz and another record, £50 million, for Fernando Torres. In the two years that followed, it was another almost-£160 million.

In all, 37 players have been brought in for at least £20 million. Twenty-three cost at least £30 million, and six cost at least £50 million.

Given how transfer fees have spiraled in the past 15 or so years, it’s tempting to shrug this off as “big club stuff.” However, when Abramovich embarked on this campaign, it was positively staggering. Mind-blowing. Flabbergasting. This type of spending was not the done thing, and Chelsea were not a club worthy of it. And yet, here was this guy, the first foreign megabucks owner in English football, who’d snapped up an otherwise ordinary club and was putting the full weight of limitless wealth behind building a power.

Ahead of his second season in charge, Abramovich dismissed Claudio Ranieri, who’d guided Chelsea to a then-rare second place finish in the league. In his place came the man who’d eliminated Chelsea on the way to a shocking Champions League crown with Porto: José Mourinho. That’s when the party really kicked off.

2004-05 and 2005-06 brought league titles — just the second and third in club history, and the first back-to-back English top flight titles by any club since World War II. The following year, it was the FA Cup. However, early in his fourth season, after disagreements with the boss, Mourinho left “by mutual consent.” Some of this, of course, was surely Mourinho being Mourinho. At the same time, it also offered a sneak peak of what managers could expect under Abramovich. In the 14-and-a-half years since Mourinho’s first departure, Chelsea has employed 11 different managers (including Mourinho again), for 13 managerial stints.

Prior to Moneyed Man City, the new Chelsea was not welcomed by opposing fans — they were known for a time as “Chelski,” and serenaded with chants of “you’ve got no history” (and stuff less flattering) by Liverpool fans. For better and for worse, however, Abramovich followed through on his promise to build a sustainable winner. There were, of course, the massive transfers and wages, but also a new state-of-the-art training complex in Cobham (in Surrey, just southwest of London), a youth academy that’s churned out talent (for both Chelsea and others), and England’s biggest trophy haul (18) since the 2003 takeover: two Champions Leagues, two Europa Leagues, a UEFA Supercup, five Premier League titles, five FA Cups, and three League Cups.

Where Does Chelsea Go From Here?

So, the man who was once the wealthiest in both Russia and Britain, with a peak net worth of $23.5 billion in 2008 (and around $19 billion in October 2021, and $13 billion now), is left with a freezer full of assets, and unable to either conduct transactions in the UK, or leave. Where does that leave his top-three Premier League team that’s likely to qualify for the final eight of the Champions League?

Short-term, in the interest of allowing Chelsea to keep operating and carry on with its season — currently impossible under Abramovich’s stewardship, as, again, he’s basically not allowed to touch money — the club now effectively belongs to the English government, which has issued a special license to allow for certain day-to-day operations:

- Hosting games and traveling to away games, with reasonable associated travel and logistical costs;

- Payment of wages to all players, coaches, and staff;

- Payments related to player loans and sales that were agreed to before March 10; and

- Continued collection of its share of Premier League broadcasting fees;

But not:

- The sale of any additional tickets (season ticket holders and fans who’ve already purchased tickets to upcoming games will be allowed to attend those games);

- The sale of any merchandise.

Longer term, the huge question looming over this situation is: Can/will Chelsea be sold?

According to a report by The Daily Telegraph’s Matt Law… yes*?

“A new license would have to be granted for a sale [of the club] to take place, as the existing license prevents it. That could happen if a sale is deemed to be in the best interests of Chelsea and does not benefit Abramovich.”

Stoppage Time

For some time to come, most discussions of the Abramovich era at Chelsea Football Club will focus on this final episode — the desperate attempt to turn the club into his own personal “go bag,” and the geopolitics that necessitated that Hail Mary. And rightfully so.

However, regardless of circumstance, that a sale was planned at all was significant, in that it marked the end of a defining era in world football.

Roman Abramovich is not a one-off, but he was the first of his kind. Of course, Middle East oil money, Chinese industrialists, and the American fleece vest brigade would invariably have found big time sports as a means of (milage will vary) laundering money and reputations, spearheading real estate development plans, or simply squeezing out returns. However, at a moment when the world’s most obscenely wealthy couldn’t be bothered with thoughts of not only buying, but earnestly operating a soccer team, Abramovich did.

It would be incredibly naive to think that he did so entirely out of some deeply held belief in “the magic of the FA Cup,” but it’s impossible to deny that building something of genuine quality wasn’t somewhere in the equation. Sure, with or without Abramovich, PSG and Man City still eventually happen. At the same time, it was Abramovich that provided the Qataris and Emiratis with a blueprint: Make a monumental splash financially, absorb the “buying trophies” and “nouveau riche” quips, start winning domestically, keep spending, break through in Europe (harder than it sounds, eh?), and just wait for the walking AmEx Black Card to come along and turn you, if not into a part of the old guard, at least into “old new money.”

Bear in mind, much of this is not meant as praise:

- The upending of the sports financial structure that Florentino Pérez started with the original Galacticos at Real Madrid, Abramovich’s unending supply of cash carried past a point of no return (though, to the extent that players themselves received more money, this is not a bad thing);

- In response, the sport’s powers-that-be conceived of Financial Fair Play (though the manner in which it’s “enforced” speaks loudly about the authorities’ concerns over sources of funds);

- More egregiously than any other English club, Chelsea has hoarded youth players, loaning them out to clubs near and far. This serves only Chelsea, as the players have no say as to the club and system in which they’ll develop, and smaller clubs that do benefit from these talents do so on Chelsea’s terms, deprived both of the pride of claiming effectively homegrown stars as their own, as well as the difference-making transfer fee when that young star eventually moves to a bigger club;

- Despite not having entered football with money as a primary motivator nor truly needing the money at that moment, Abramovich supported (initially, at least) the ill-fated European Super League. This can only be seen as one of the sport’s ultimate new money success story clubs trying to slam the door shut to a VIP room that, not long ago, would never have been opened to it.

For better and for worse, huh?

This is, more or less, where this leg of our story ends.

Abramovich now faces a decision between: Allowing the British government to dictate every detail (including who receives the proceeds) of a sale of Chelsea, or simply hanging on, allowing Chelsea to operate (and deteriorate) as something of a zombie club.

It’s a strange way for this era to end, though when you think about it, given the way in which it began and the everlasting marks it’s left on the game, calm and quiet were never in the cards.

[…] Emile Avanessian. Emile writes for Hardwood Hype and more recently has done a piece on the Roman/Chelsea situation, Catarina Macario, and Barca’s third kits over the […]

[…] Emile Avanessian. Emile writes for Hardwood Hype and more recently has done a piece on the Roman/Chelsea situation, Catarina Macario, and Barca’s third kits over the […]

[…] Emile Avanessian. Emile writes for Hardwood Hype and more recently has done a piece on the Roman/Chelsea situation, Catarina Macario, and Barca’s third kits over the […]