Over 120 years old, El Gran Parque Central is one of the most important stadiums in all of South America. In addition to hosting the first-ever World Cup match, it has a history within its structure that goes way beyond just hosting a team and holding a large capacity of fans.

Founded in 1899, Club Nacional de Football is one of South America’s most historic football clubs. Like many other teams of the pre-FIFA era, Nacional walked the long road from amateur to professional soccer, and paved the way for some important moments in Uruguayan and South American soccer.

Nacional was the first team in Uruguay to allow locals to play, which up until that point, was an elitist sport for the English and European immigrants who were settling in the small South American country. As a result, the club was not permitted to join the Uruguay Association League, which was governed by foreigners (Albion F.C., CURCC, Uruguay Athletic Club, and Deutscher F.K.). Due the team’s exceptional performances in friendlies and talks of it joining the Argentine league, the UAL was eventually forced to allow Nacional to join, making it the first professional Criollo club in Uruguay.

Nacional has gone on to win an incredible number of 124 domestic and 22 international championships, including three Copa Libertadores and three Intercontinental Championships, which equate to Club World Cups.

A team of such rich history needs a stadium to live up to it, and El Gran Parque Central does just that — not only on the pitch but off of it as well. El Gran Parque Central is a part of the fabric of a hard working community, a fan base that literally painted the grounds, and above all else a jewel of what soccer was like long before social media and fancy marketing.

El Gran Parque Central: A Stadium Built By the Fans

Martín Sarthou, Nacional’s communications manager, describes El Gran Parque Central as “essential for the values the club tries to transmit. Nacional has its people, its territory, its home. Nacional is Uruguay, but the hub of those ideals is at the Parque Central.”

Located in the neighborhood of La Blanqueada in the heart of Montevideo, the Gran Parque Central opened its doors in 1900. Unlike many new modern stadiums that are built around the world, El Parque Central is a fundamental part of Nacional not for how flashy it is or its amenities, but rather the history it holds.

“Moving or even tearing down the stadium to build a new one is simply out of the question,” Sarthou said. “None of our fans would stand for that. We may not have the most modern stadium in the world, but our halls, our walls, and our locker rooms have a history that is too important to simply tear down.”

El Gran Parque Central wasn’t always the jewel at the center of Nacional, however. During several administrations, the legendary stadium was semi-abandoned. Its last facelift coming in 1974, the stadium would go unused for nearly 30 years until 2003 when the club decided it wanted to avoid paying rent in the Estadio Centenario and reclaimed their home ground once and for all. The stadium reopened in 2003 and since has expanded to 34,000 seats, with plans to grow that to 40,000 by 2030 in order to become FIFA-sanctioned.

One of the most important aspects of the reimagined El Gran Parque Central was the participation of the fans. From the initial project to bring the stadium back to life in 2003 to the latest phases of its expansion, fans have come out from all walks of life to roll up their sleeves and paint the stands and help with the stadium renovation. It is not uncommon to see whole families helping to do this for free. Nacional is a symbol of solidarity and unity among their supporters. No matter if rich or poor, the fans of Nacional unite for the club.

The First “Hincha”

El Gran Parque Central was the home of the first “hincha,” the South American word for supporter. Prudencio Reyes, a saddler by trade, began to work for Nacional as a team handler during the 1900s. By today’s standards he would have been an equipment manager, whose primary job was to inflate the game balls. In Spanish, the position translates to hincha pelotas.

Besides performing this task for the club he loved, Reyes also attended games and began yelling during the match. “¡¡Nacional, Nacional!! ¡¡Arriba Nacional!! ¡¡Vamo’ arriba Nacional!!” was one of the many chants Reyes would scream during the match. At that moment in time, soccer was seen as a recreational activity and seeing someone act like that was very shocking. Eventually, fans began to ask who that “madman” was, and the answer was, “That’s the hincha.”

From then on, the word hincha has been used all over the Americas to identify the most passionate of fans. Reyes’ legacy has not been lost, and he has a statue of himself at the grounds as a tribute to the fans who leave it all on the field just like the players they support.

A Stadium of Culture

Another statue that one can find at El Gran Parque Central is that of famous tango singer Carlos Gardel. While there are many legends surrounding where exactly Gardel was born — France or Uruguay — one thing that no one can deny is that Gardel, an avid soccer fan, had a love for Nacional.

A statue of Gardel can be seen sitting in the stands of the José María Delgado section, and Gardel and Nacional had a very important link.

“Gardel would regularly attend games, he would also go to El Parque when Uruguay would play international matches in the stadium,” Sarthou said. “In the 1930 World Cup, Gardel sang and ate with the Uruguayan national team during the competition. Those photos that we have of him at the stadium made fans want to immortalize his presence in the grounds. Gardel was an icon of popular music of the Rio de la Plata and Uruguayan culture. He chose El Parque Central to watch his favorite sport and Nacional was the team he identified with at the time. He had to have his place in the stadium and is a part of our historical tour of the facility.”

Another influential figure in the club’s history put his touch on the stadium as well. Former club president and poet José María Delgado won 19 championships during his time at the helm of the club, and one of his wishes before he died was for a window that would allow him to watch his beloved Nacional play from heaven. The club heeded those words and built a window that is opened on game day so that Delgado and any other Nacional fans no longer with us can watch their club play from wherever they are.

Not Just A Stadium, But the Birth of a Nation

El Gran Parque Central is home to one of the most historic events in Uruguay’s history. In October 1811, during the Uruguayan war for independence, “the Orientals,” as the rebels were then known, broke an accord they had with the Spanish and retook arms to fight for independence. It was there that José Gervasio Artigas was named leader of the Oriental army and eventually became “the father” of the fledgling Uruguayan nation. Nacional’s colors — white, red, and blue come from the flag of Artigas, as Nacional prides itself on being the first true Uruguayan soccer team founded by nationals.

Another strange historical occurrence was a political duel that took place within the stadium grounds between two important political leaders of their day, José Batlle y Ordóñez and Washington Beltrán. Due to a newspaper article that Beltrán penned in the El Pais newspaper, Ordóñez wanted to reclaim his honor by challenging the young political leader to a duel with weapons. It ended in tragedy and Beltrán was killed, legally, due to a gunshot wound in 1920.

The Link Between El Parque Central and the USMNT

Of all the unlikely links El Parque Central has, perhaps its most unlikely is that of the United States men’s national team and the 1930 World Cup. It is in this historic venue where the United States won the first World Cup match it ever played, a 3-0 win over Belgium. Additionally, another piece of history for the USMNT also occurred in El Gran Parque Central — Bert Patenaude was the first player ever to score a hat-trick in a World Cup, as the United States defeated Paraguay 3-0.

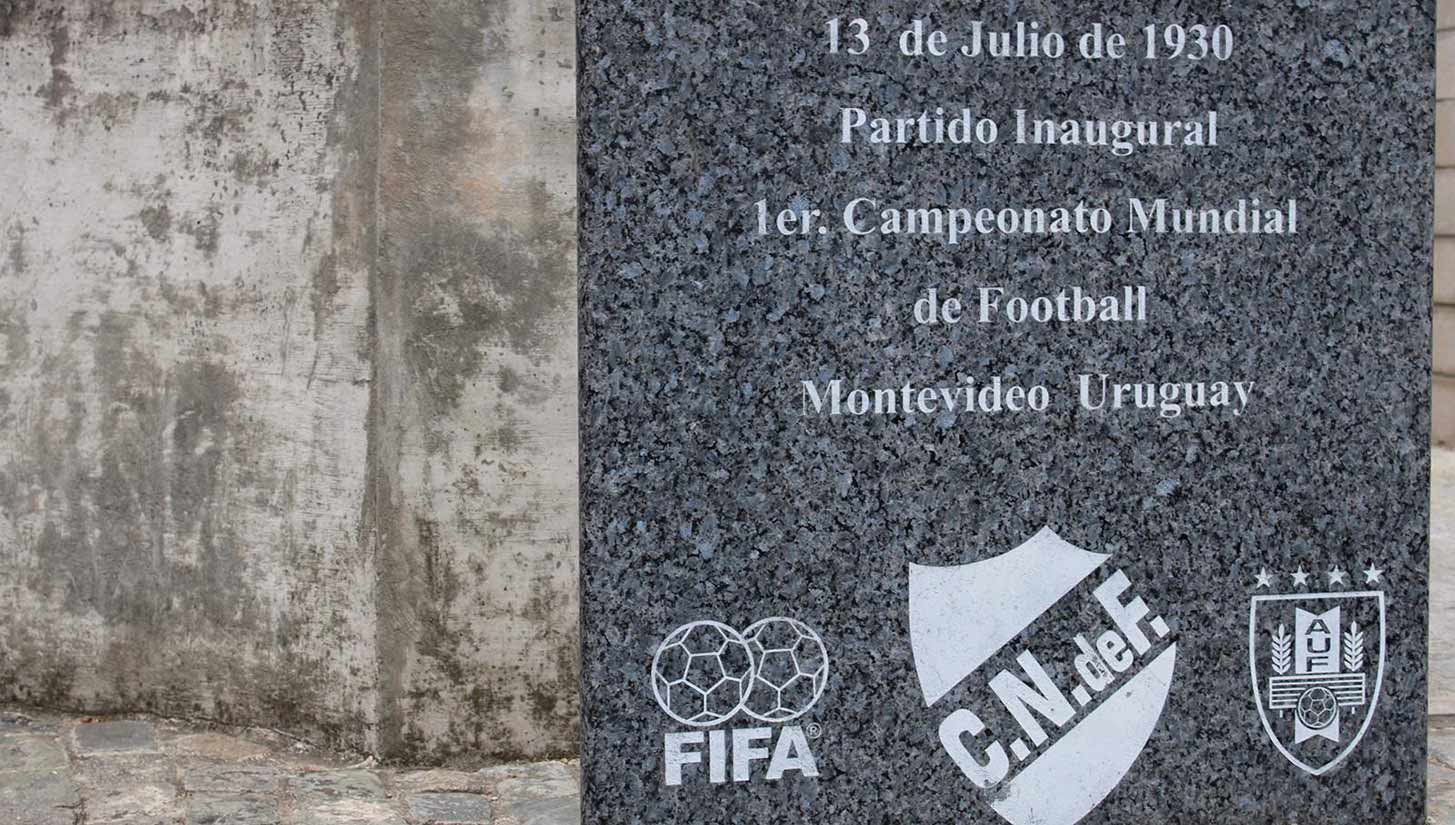

El Gran Parque Central has received FIFA acknowledgments as the first venue ever to host a World Cup match, hosting six total games in the 1930 tournament Uruguay would go on to win.

The Story of Abdón Porte

Abdón Porte played for Nacional from 1911-1918, and while he won 19 titles with the club, his story stands out as both a tragedy and a mark of history. After Porte was released by the club, the midfielder broke into the grounds of El Parque Central and took his life. While Nacional has never condoned Porte’s decision, it is a historical fact that a player committed suicide on the grounds.

The section where the supporters sit is named Abdón Porte, not as a homage, but rather as a symbol of the love that Porte had for Nacional. The club has always been very animated that it does not want to glorify the act of suicide, but they cannot erase who Porte was and what he represented to the club during his playing days.

In an age of state-of-the-art stadiums and rebrands of every kind, the historical importance that a stadium like El Gran Parque Central has reminds us every day that the origin of the beautiful game was not started by billionaires, but rather everyday hard working people, and that legacy in some cases is over a century old and is passed on to generations.

Photography by Kelvin Loyola for Urban Pitch.