They took the world by storm last summer with some of the most unique and head-turning designs in all of soccer. But what went into the making of the Venezia FC kits? We sit down with former Venezia creative director and Fly Nowhere co-founder Diego Moscosoni to discuss how the agency and club came together, leaving Nike for Kappa, and the surprising reception (both good and bad) the kits received upon their release.

If luck is where preparation meets opportunity, Fly Nowhere co-founder Diego Moscosoni is the luckiest man alive.

An extensive background in fashion and design with brands like Supreme, Marc Jacobs, and LVMH, paired with a lifelong passion for soccer, Moscosoni, and by extension Fly Nowhere, has created some of the best soccer-fashion crossovers we’ve seen. But perhaps best of all is the collection they made for Venezia FC. Yes — that collection. The one that set the internet ablaze upon its unveiling last summer.

Newly promoted to Serie A, Venezia FC’s home and away kit reveal turned the relatively small club into one of the hottest in the world nearly overnight. But while the fantastic jerseys seemed to come out of nowhere, like all feats of success, this journey was years in the making.

It started in 2016, after Venezia was bought by an American ownership group. Through mutual connections, Ted Philipakos, an executive with Venezia under the new regime, on-boarded New York City-based Fly Nowhere to help build the club’s brand and image. Despite working on a few initial ideas, club instability prevented any of them to come to fruition and Fly Nowhere moved on to other projects elsewhere.

In 2020, Philipakos, now Venezia’s CMO, brought Fly Nowhere back and appointed Moscosoni as the club’s creative director. In the midst of a pandemic, the Fly Nowhere team got to working on the club’s brand direction, which included some of the initial ideas from 2016.

One of the biggest decisions the club made was leaving Nike for a new technical sponsor in Kappa. Among many other reasons, Nike’s rigid structure and template-based designs were not ideal for Fly Nowhere’s vision. As one example, the 2021 home kit that Nike proposed for Venezia was dismissed by the agency and the two sides could not compromise on a solution.

Kappa, smaller and therefore much more flexible in comparison to Nike, was willing to take the risk to execute the Fly Nowhere vision, and the rest, as they say, is history.

However, despite the success, Fly Nowhere is no longer at the helm of Venezia’s creative direction. The creative agency already has a handful of new projects in the works with other European clubs, in addition to having signed Canadian and Lille star Jonathan David.

To reflect on Fly Nowhere’s run in Venice, we sat down with Moscosoni, discussing the New York City connection between club and agency, the challenges and obstacles he and the Fly Nowhere team had to overcome, and the mostly positive (yet some strongly negative) reception to the 2021-22 Venezia FC kits.

Urban Pitch: With the American ownership and your background having studied in Venice, it seemed like Fly Nowhere and Venezia FC were the perfect match. How did that help in the work process between you and the club?

Diego Moscosoni: If you have a lane and you stick to your lane, things will come. You’re setting yourself up for luck, and then the lucky thing happens. Venezia is not the first Italian team I worked for, not the first football thing either, obviously. I was already working for Nike, adidas, many clubs, and many brands.

We definitely had an American connection, but even more than that, I’d say it’s a New York connection. The reason why I’m involved with it, the people that called me, the reason I was in their rolodex, was it was New York groups, New York owners — you could also give some credit to Jim Pallotta, from Boston, who was an early American into football in Italy. Jim Pallotta had a lot of entourage around him, and a lot of those people have gone on in different directions. I’m one of those people from the Jim Pallotta world, although I already had things in football before I met him. But he was a catalyst for a lot of the American stuff going on over there.

The Venezia one is more of a New York story. It was Ted Philipakos, he’s a New York guy. I’ve been living and working in New York for most of my life. My family’s from here, my grandparents were here. Also, our style of working is a New York way to work. I’ve lived in Los Angeles for a long time, it’s different over there.

New York is close to Europe in that sense. Whereas, I don’t know if it’s so much an American story happening in Italy, as much as it is New York is a European city. We’re already connected with Europe. All of our clubs and restaurants are run by French or Italian people, our trade back and forth with the UK, Germany, all these companies are all here.

Barcelona has offices here, Bayern Munich has offices here, most of the big football clubs have offices here. This is kind of the gateway to Europe. It’s probably why I would be in the front of that wave to get into this. But it has now spread beyond New York. Everyone in America has had more time to digest this and get involved. So it’s spreading.

As someone with a deeply-rooted passion for soccer that has also worked with multiple big brands and clubs, how are you able to balance the pure love for the game with its commercialization?

There’s layers to that question. Obviously, commercialization is what New York does. That’s a New York thing. But New York also has a long history of subcultures. New York has created so many things that have spread around the world over the past 100 years.

Regions aren’t as important as before, but up until the internet, New York had a heavy influence in not only creating subcultures in music, fashion, or whatever, and incubating them, but also taking ideas from around the world and putting them into cultures.

First and foremost we come from a subculture background in New York. We come from working with things like graffiti, hip-hop, and punk rock that existed before there was an industry to commercialize on it. Those things started for different reasons, because there wasn’t an industry at that time. I try to always remember that when I’m doing stuff. Football is something that I was playing when I was 4 years old. I didn’t learn about commercialization until I was like 24.

There definitely is a tension here, where New York is the most cultured city in the world sometimes, and it’s also the most commercial city in the world sometimes. And that’s the costly challenge of this place. I try to be mindful of that, because I don’t want to disrespect the heritage of New York and the subcultures that created me. If there wouldn’t have been graffiti, if there wouldn’t have been hip-hop, if there wouldn’t have been punk rock, I would not have had a job. I would not have worked in fashion, I would not have worked for Supreme or Louis Vuitton. Those things were my school, so I always try to remember that.

It’s easy to bring that idea right into football. Because football is big and massive like New York, it has everything that you want. You just have to go to the part that you want. Not that there’s any right way to do football, I just know where our lane is, and where we feel comfortable. We get more comfortable in our lane as time goes on. It’s a never ending challenge.

And you can tell through the work who knows where their lane is versus who is trying to capitalize on something that they might not fully understand.

Because a lot of the younger generations right now are really talented, and they have a lot of access to information — I try to tell people it’s dope to see everything, but then also it’s good to take time to pick things that you really want to dive into deeper. The internet is a mile wide and an inch deep. Sometimes I think that’s kind of like millennial thinking. And now, Gen Z, and the new guys even below them, are going to realize that specialization has power.

You’re going to see people going in all these different directions, and you’ll want to go with them too, but if you punch through that, and stick to your thing, eventually the world comes back around to your thing. I really believe in specialization, I’m trying to get more specialized. But also, balancing it with not being rigid, learning new things, and trying to collaborate across generations.

Going back to Venezia — you had originally been brought on to work with the club in 2016, but due to instability with the club, the partnership was short-lived. What was it like getting a second chance, and how were you able to incorporate some of the original ideas you had the first time around along with some new ones?

It was definitely a gift. It’s satisfying to be able to come back and put some closure to some things that have been opened. We definitely spent a bunch of time in 2016 researching and even designing. A few of the designs that you saw this year, different versions of them were created in 2016.

Even before then, I studied in Venice as a kid in an exchange program in the late ‘90s. I was already familiar with Venezia but through the Biennale and through art, because I’m an artist and am interested in art and the history of Venice. I didn’t even know that they had a football team at that time, and I lived there. So it’s amazing to come back and have all of my worlds come together in this one city. It was a dream.

I was ready for it and prepared to jump into it, but not because of my knowledge of the football club. If anything that was limited. I had met Paolo Poggi and some of those guys, and they taught me a lot of stuff. But really, I just had a lot of appreciation for Venice the 1,600-plus-year-old city, and all of the weight of what that means to typography, to print making, to art, to glass blowing, to food, to global trade, to nautical developments, to empirical developments. It’s a micro Rome. It reigned across huge parts of the globe for hundreds of years. I was already fascinated with that stuff and spent a lot of years on it, and so when I got to put that energy into a football club, I mean, I must be the luckiest guy in the world.

It’s crazy how not only did all of those interests of yours converge together at the right time, but Venezia was also promoted to Serie A as well.

That was good luck. I watched those games. I was in those playoff games. Yeah, knock on wood. That was magic.

Did it seem like everything in your life up to that point had been leading to you being able to work with Venezia FC?

Again, only a small part of that has to do with me. I definitely made my fingerprint on the club and on the city, with Ted Philipakos and the Fly Nowhere team. And with the trust of

, and the trust of a lot of cool local people there that showed us the keys to the city.

But yeah, I would say it’s more of Venezia’s karma, because the city has probably been waiting for this moment and deserving of this moment for a long time. It’s more of a restoration project to me. To restore a historical object back on its natural path that it fell off for some reason.

There were some roadblocks that working with Nike presented in terms of executing your vision for the 2021 jerseys. Can you go into those a little bit?

I think any disagreements in strategy with Nike are not based on anything personal or even local. It’s two parties that are not set up to work together very well. Mainly because Nike is geared for much bigger, much more template-based operations. And when they do do unique creative things, they need a lot more time to navigate and do it. It has to go through a lot more approval processes and bureaucracy, and therefore they save that for the biggest clubs. PSG, Inter, they get that kind of service.

With the tiny clubs like Venezia, it’s essentially a template program. It’s not really even Nike doing much at all. We attempted to offer some compromises, but their system just doesn’t have the room for that. It’s mainly because there’s not enough time.

At the same time, Venezia is small, but it cannot be treated like a small city. Because of the aforementioned 1,600-year history, and because it’s tied with or probably just behind Milan and Rome as the most-visited city in Italy. It’s one of the most famous cities in the world. So it has a unique challenge, because it punches way above its weight in brand, but it’s not big enough locally to support Nike or these big companies dumping a bunch of money into jerseys that they can’t sell.

When I got there, there were still jerseys from Nike from 2017, 2018, 2019, sitting in the warehouse that we couldn’t sell. We couldn’t sell Nike’s minimum quantity. So there’s a production issue that needs to be solved, and then there’s the design issue, which is that we designed this whole thing on a quick navigation — about 60 days — and Nike needs a minimum of 12 months. So it is what it is. We just had to shop around, and Kappa was one of the four other contenders that had a dealer fit, and that was willing to take the risk on of doing it so late.

How has working with Kappa been different, and what was it like working under those tight deadlines, especially during the pandemic?

Yeah it was definitely super stressful with all those deadlines. Obviously this is in the middle of the COVID pandemic, which was even more locked down and strict in Italy than in America. So you had to get permission, if it was a red zone, orange zone, yellow zone, to leave your house, to go to the grocery store. You had to have papers when you walked around. In a town like Venice, there’s police checkpoints on the bridges, you’re trapped on a part of the island to even get to the grocery store.

There’s a lot of these extra layers of pressure that were put on us in addition to the speed. Kappa was set up with the right appetite for the risk and the right production setup to navigate quickly, where we fit really well in that sense.

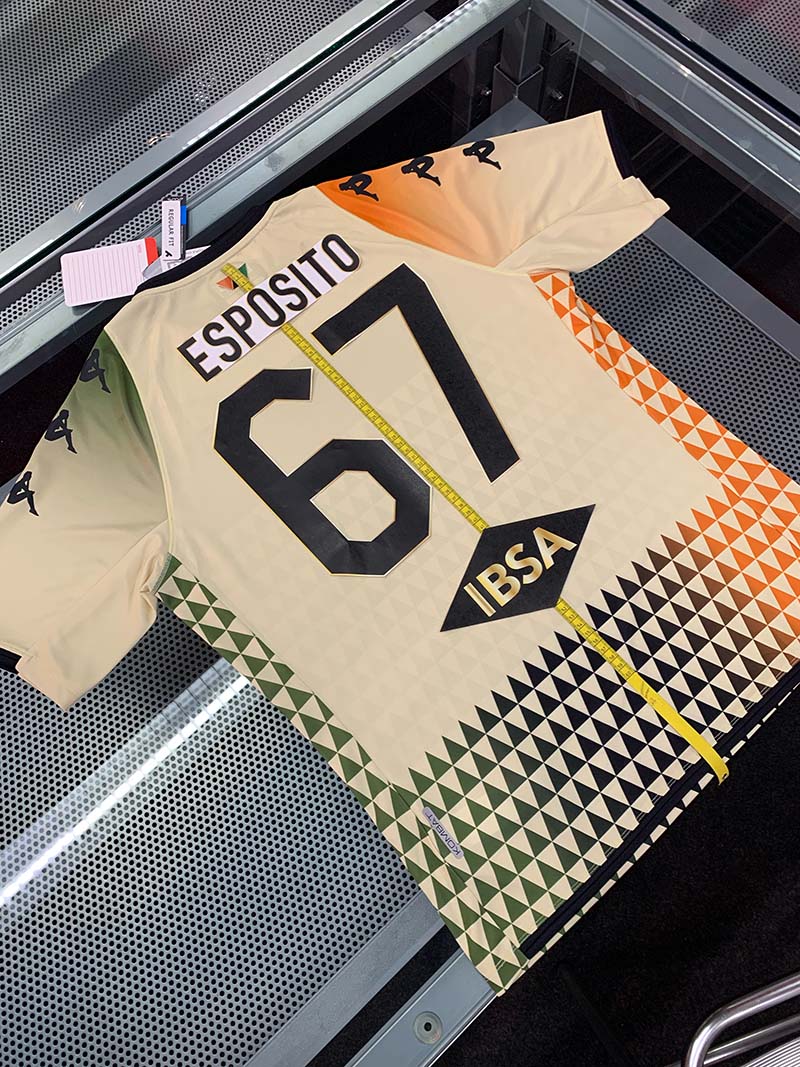

At first, they were pretty skeptical, which they should be, because we were in Serie B — we never designed this for Serie A. It was already done before we got promoted. If anything Serie A destroyed our production release plan and created a whole bunch of extra issues. For them to dive into a Serie B team this late was a risk, but eventually they realized that it was a calculated risk. Being in Italy, it was the perfect fit. Even though it’s made all over the world, their thinking was in sync with what our needs were in Italy and in football. So they had more intimate knowledge and appetite to get into the weeds of it. That was really helpful.

What was the turnaround time like?

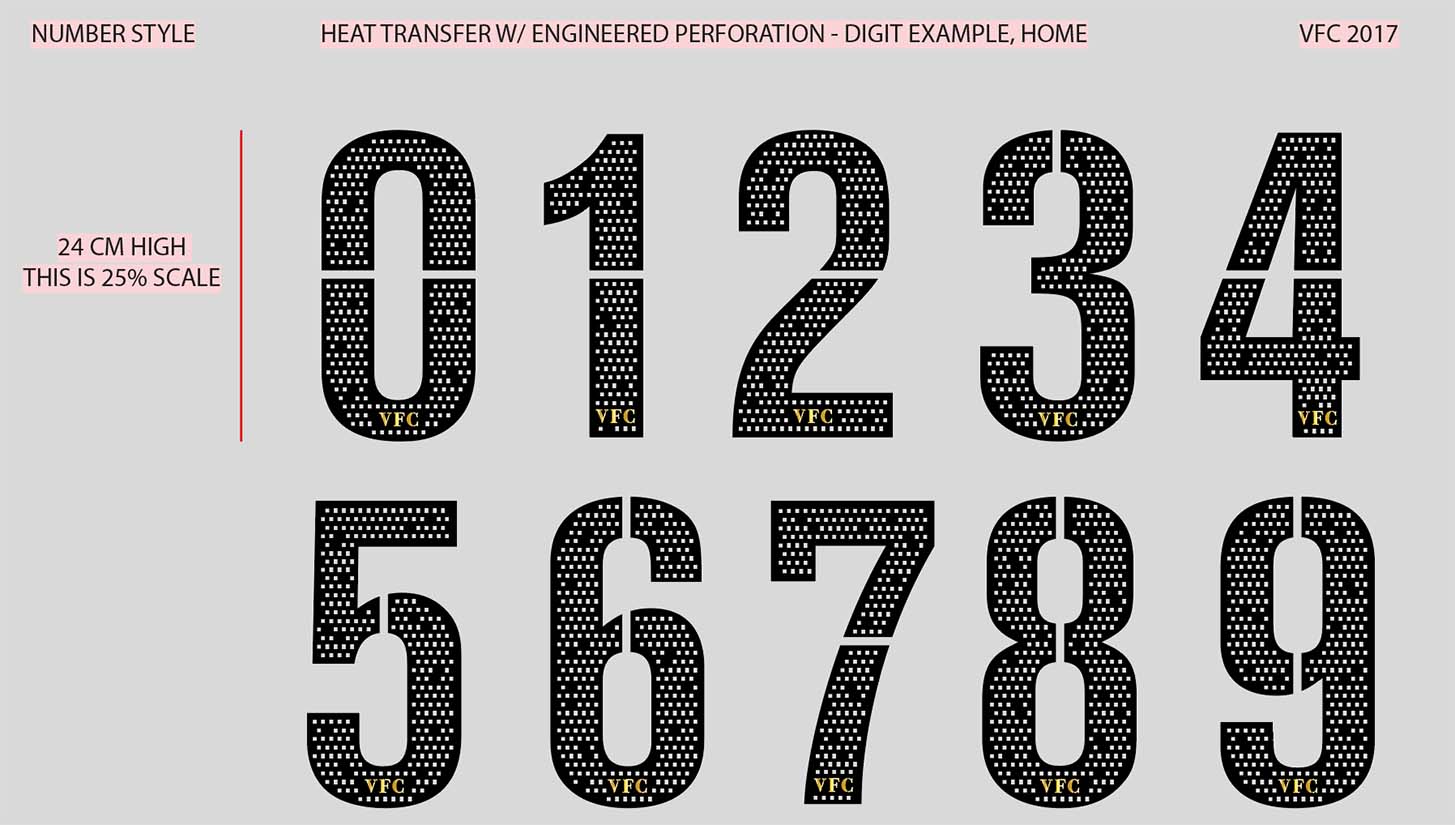

Kappa is super fast, although they don’t build the whole complete thing. The silicone badges and all of the other bells and whistles that you notice, the Venezia ones are better than the other Kappa ones. That has to do with us going a little further with using our own supplier for the embellishments, numbers, all that kind of stuff.

So it was a partnership between three companies to get the Kappa stuff done in time. But Kappa is set up for that. They’re fully logistical masters. They get back quickly and know how to solve problems about what we can and cannot do. It’s really a puzzle to put together, and Kappa is the puzzle masters. They’re flexible — the opposite of how a larger company like Nike would have to operate. Nike has committed their budgets a year in advance. They can’t spend resources on puzzles.

And we had a puzzle to solve, with Ted Philipakos, Fly Nowhere, myself, and Duncan the owner. We all had to take calculated risks. It’s a risk even for Duncan to leave Nike, which is a guaranteed thing, while Kappa is a puzzle which may or not make it in time. I think Kappa was aware of that and ready for that, and knew how to pick the lock with us.

Was the Nike deal expiring or did you end that partnership early?

The contract had already expired. We were debating on whether to renew or find another brand. For whatever reason, when I landed there at the beginning of the pandemic, they hadn’t made the decision yet, whether they wanted to continue with Nike or not.

They were already late for Nike regardless. Even had they continued, the Nike setup was way late. At that point it was kind of like, well if we’re going to be late anyways, and there’s all these challenges, might as well take a leap of faith and try to get some bespoke custom stuff. And the main contention point, the breaking point for us, was that I insisted that we needed four kits, and that we needed to do more kits.

Nike wouldn’t give us more. All we want to do is buy more, and they were like, you can only buy two. And if you want three or four, that’s hard for us and we have to figure out a way to do it. They had no clear answer for that. My vision of the future of football is that every team has four or five kits, or however many they want. It’s the football club’s choice, not the technical sponsor’s choice.

So at that point you knew it wasn’t going to work out with Nike.

It wasn’t the right time. I think when Venezia is in Serie A for like 10 years straight, they’ll go sign a five-year Nike deal, and on year two it’ll probably be the best shit in the world. Because Nike makes the best shit in the world — when they want to.

The Venezia kits are very streetwear friendly by design. How did your previous experience at brands like Supreme and LVMH inform some of the design decisions you made, and what are your overall thoughts on the blurring lines between football and fashion?

First, my take on streetwear is, streetwear is now the label of an industry, but that industry didn’t exist when Supreme started, or barely even when I started. There were different generations of it — first it was just kids wearing and appropriating things from other places. Skateboarders were wearing Jordans in the early ‘90s in New York. But Nike didn’t do a Supreme x Jordan collaboration until like 25 years later.

So there’s always been kids making their own style. And that’s the basis of streetwear. So when people say, “Streetwear is dead,” and all that kind of stuff, it doesn’t make any sense to me. Because there’s always going to be new kids and they’re always going to dress how they want. That’s streetwear.

Now the streetwear category to me is really a derivative of Supreme itself. Hypebeast and all these other brands are the derivatives of an older generation of things, which are Supreme, and some things that have happened in Japan. Which to me are the forefathers of the current streetwear industry. I guess London had a lot of those brands as well. So it’s always been a London, New York, Japan thing.

But then also you had Shawn Stussy and the surf and skate culture of Southern California, which was a huge part of that and its own contained thing. They all kind of come together in the mid-late ‘90s, as a culture, and even started to blend into Japanese things like toys and other stuff. So that’s the streetwear that we’re now into, maybe Gen 3 or Gen 4 of that industry.

So as far as how that applies to football, again, football is just like surfing, it always had its own things like that. So it wasn’t a big leap to do this with football. When we designed for Supreme, we don’t really make a conscious attempt to try to pander to what the industry is doing this year. It’s classical things and a classical process. It’s meant to have meaning.

With Venezia it’s the same back-and-forth process. What would a football authentic thing look like first? And then, what would a naval city with 1,600 years of history, how would they approach it? But then the final part of it is, how do we make this contemporary and mash it up? That mash-up sauce, that balance of what to do and what not to do, that’s the part I do. And that’s something that’s hard to put into words, but it’s knowing when not to go too far. When to reel it back in, and it’s also knowing when not to self indulge in my own creative expressions.

A little bit of me is in there, but then I need to pull me out of it and think about the local guy in Mestre, who doesn’t like streetwear, who’s going to be offended by the streetwear. Make sure there’s something for him. And that’s the whole reason why we did four kits. They’re all different on purpose. One is for your mom, one is for the fancy guy that wants to look rich, one is for the down-to-earth ‘90s streetwear enthusiast or the football jersey collector enthusiast. And then the other one might just be artistic. Hopefully someone who doesn’t care about football might be drawn in because it reminds him of glass blowing and the Biennale.

Can you talk about the reception of the Venezia collection a little bit? Obviously you had some idea that it would be warmly received with all of the work that you put into it, but did you imagine it would be this widespread?

That was also a mixed bag. It was the most positive reception I’ve ever had in my life, and at the same time as it was the most aggressive, negative reception I’ve ever had. Even more extreme than a Supreme release, where people are always going to hate on Supreme.

This was even more insane than that, and more disconnected, where the majority of people were blown away by it and surprised in a good way. And then there was a very small group of people that are maybe more locally embedded and maybe more rooted in even one section of the stadium, who completely felt the opposite.

They made banners that said, “Fly Nowhere, never again.” They went out of their way to choose us as some kind of an enemy. When first of all, we don’t care. Second of all, we’re just doing our job. And third of all, it seems like it helped. Because you made a lot of money, and brought a lot of momentum and attention. But it was a huge disconnect between a very small group of people who literally were hunting me down on social media. But that goes with the territory. That’s football and that’s Italy. I take the good with the bad, and it is what it is.

Wow, I didn’t even know there was that strong of a negative reaction to the jerseys.

I hope that was only a knee-jerk reaction. And maybe the first two or three weeks that was the case, and maybe once they had time to digest it and research me and Fly Nowhere maybe they had a change of heart and realized that we’re not the hand of Modern Football. We’re the opposite. We’re a tiny boutique of guys from the streets.

I don’t have a college degree, I didn’t graduate from high school. I’m from a graffiti gang, just like they’re from a football gang. I don’t claim to be a Venezia person. I’m a guy doing my job for whichever club calls me next. Certain clubs I won’t work for, certain brands I won’t work for, maybe. Mainly just based on a fit.

But I would not accept that anyone would tell me I don’t fit in the city of Venezia. Because I put in 20-plus years there. I would accept if they told me that I don’t fit in the Venezia curva of the stadium. Cool. I’ll sit in the other section of the stadium. Or I’ll sit outside the stadium and listen to the sounds. It doesn’t matter to me. I’m not there to ruin their party or come into their territory. If I’m not wanted I’ll leave. I got other shit to do besides argue with 300 people. That’s the internet, bro.

Yeah, and there’s obviously a lot of emotions that come with soccer fandom, especially when something new comes.

I don’t blame them, I knew there would be some pushback. Even within the staff of the club there was tons of pushback the entire time I was there. But again, I worked for many bureaucratic companies in Italy, that’s not new. There’s always going to be people protecting their territory, and I respect that. We try to move with cultural sensitivity, up until a point. And if you’re unreasonable, then you’re fucking with New Yorkers. It’s that simple.

Interview edited for clarity and brevity. Photos courtesy of Fly Nowhere.

Follow Fly Nowhere on Instagram to stay up to date with their latest projects.

Editor’s note: A former version of this story stated that Diego Moscosoni is the current creative director at Venezia FC. The story has been updated with his correct title as former creative director. Additionally, to clarify, Venezia FC’s decision to leave Nike was not made by Moscosoni, rather it was made by club executives.