By Christine Kwon / Guest Contributor

The pinnacle of professional football, with all of its glory and glamor, is the dream job of countless kids (and adults) around the world. But the reality is the majority of pro footballers aren’t playing at the very highest level. They may work just as hard as the big names, but their playing conditions and salaries are much more modest. While you might have trouble sympathizing with those who get to play a game for a living, we spoke with ex-pro and Brazilian national Bruno Meyer Simoes on the non-stop grind of lower division football, and the incessant hunger Brazilian footballers possess.

Bruno Meyer Simoes grew up with a football field as a backyard. Not only that, a paintball park, a basketball court, and a volleyball court. Suffice it to say, he comes from a very active family. A family of elite athletes, in fact. His father played for São Paulo FC, his two uncles were pro footballers, and his mother a pro volleyball player (and goalkeeper). Bruno’s younger brother, who he describes as much better than him, was offered a football contract at the age of 15, which he turned down because he just wanted to play for fun.

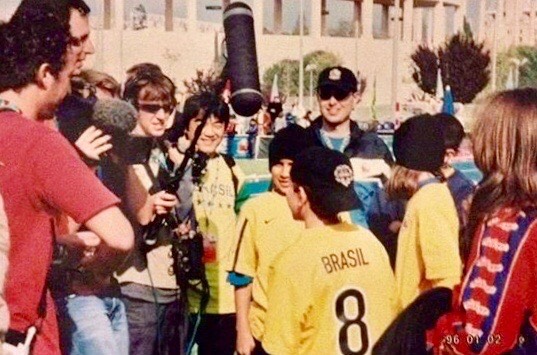

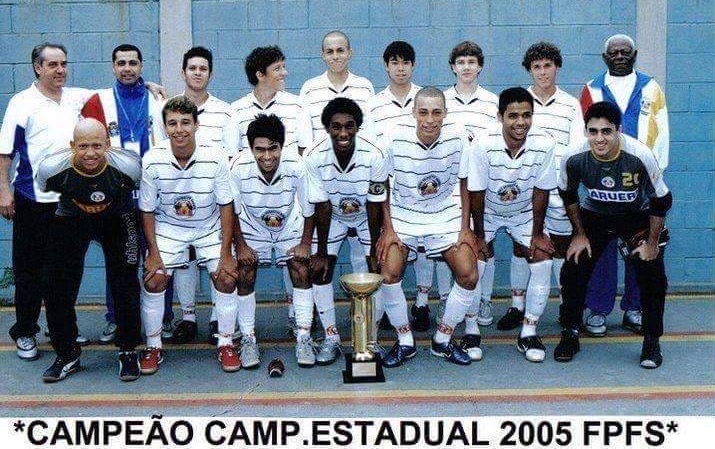

Simoes himself has had a lengthy career in professional futsal and football. He started at the age of 12 with GR Barueri, a futsal club where he turned pro at 17. He was on the U13 Brazilian national futsal team, and at 15 spent a year training with Corinthians alongside Willian. During high school, he would practice in the daytime and go to night classes with adults. In college, though, the coursework and training became overwhelming.

“You have a chance to play professional for a long time,” Simoes remembers his father telling him. “But at the same time, they can come and say, ‘You’re not playing anymore.’ So what is better?”

Even for a talented athlete, football as a future is not a guarantee. So Simoes made the hard decision to put the game on hold and get a degree first.

After graduation, he worked for his dad’s lighting company, but as expected, football was calling him. He started training with Brasilis FC, a professional club based in Águas de Lindoia. Two years later, he got a call from a friend in the United States who asked if he wanted to play indoor soccer. That’s when Simoes found himself in Oklahoma with the Tulsa Revolution, and later the Ontario Fury in California. In 2017 he went to Germany to join FCA Darmstadt, a fifth-division team. After a brief stint there, he retired to settle down and be closer to his wife. He now is hoping to become a coach.

We sat down with the Brazilian national to discuss what it really takes to be a pro, and his path to a life spent playing the game.

Urban Pitch: What was your daily training schedule when you were playing pro?

Bruno Meyer: Mondays are more light training because we played on the weekend. Tuesdays are more technical — passing, possession, finishing. Wednesday is tactical, and Thursday small-sided games and scrimmages. Fridays are set pieces and a fun game we call rachão.

Every team is different but when I used to play, the breakfast starts at 9-10 a.m., practice 10:30 a.m., 1 p.m. lunch. And we are free the rest of the day, but some days we have video sessions where we watch and talk about the upcoming game. We have appearances, too. But it depends on the level and how organized the team is.

At what level in Brazil or the U.S. do you need to play in order to make a living? Do most players have another job? Can you work and train at the same time?

In Brazil you need to play at least first or second national division. In the U.S., it’s hard to say because some MLS players still can’t have a stable life because they don’t offer good contracts to everyone. Some players get millions of dollars and others $50,000 a year with only a one-year contract, so the next year they are unsure of their status with the team.

What makes Brazilians so good at football?

I think because we play the whole day. We go to school, you’ll be playing with friends at lunchtime. You get out of school, you go to your house, you’ll be playing with your friends in the street. And the coaches, they let us play free. Other countries play all the time too, but they’re really tactical, like England. In Brazil, you play free. And every time you play it’s really competitive. Like you bet a Coke, so we play where the winners get a two-liter Coke.

“I think the connection for soccer is because everybody in Brazil, for the most part, is poor. They don’t have any money … Because of this, everyone plays like it’s for everything.”

But Brazilians seem to have a little extra something. A deeper connection. How do you explain that? Is it a mystery?

I think the connection for soccer is because everybody in Brazil, for the most part, is poor. They don’t have any money. So soccer, it’s not an “easy way,” but it’s a way to take your whole family out of a bad situation. Because of this, everyone plays like it’s for everything. Other countries, they don’t have the same life that Brazilians have.

So I think it’s this. Soccer is a way to give your family a good life. Because here [in America] you have a lot of opportunities, and Europe too. If soccer is getting boring or the coach is yelling, they can always stop and get out. But in Brazil, we don’t have these opportunities. It doesn’t matter if you don’t like the coach or anything, you keep going. Everyone wants to be the player who can take their family out. They play like they don’t have a tomorrow. They put in their head, I might die tomorrow, so I play for my life.

How do you think Brazilian national players rate when it comes to game intelligence and understanding? What are some of the biggest strengths and weaknesses in the Brazilian game?

I still talk with some players and coaches that are active in Brazil and most of them tell me that our Federation is too proud to change their mentality, so coaches are using old tactical methods and they are not trying to adapt to the new way of playing football. So our players start learning modern football when they go to play in Europe, and because of this some players struggle at the beginning and others cannot adapt and move back to Brazil. Our strength still is our technical ability, but our weakness probably is our tactical mentality. I can be wrong, but when I watch the Brazilian league, I don’t see any organization or tactical understanding.

Who did you want to play like when you were growing up?

Ronaldinho’s my hero. So I liked to play like him — magically. I had a really good, tight touch. I was really quick with the ball. Nobody played like him though. He did some impossible things for that time. It’s like when you go talk to the old guys about Pele and Maradona. You have players better than those players today but at the time, what they did was from another world. Like Messi today, what he does nobody has done before. He’s special. Ronaldinho’s the same. When you had this game that was really tactical, he came in and started dribbling and doing magic. And Brazilians, we love players that go 1v1 and do nice, fancy stuff. So him and Ronaldo were unusual to see at the time.

What’s the coaching style like in Brazil, and how is it different from everywhere else?

They let you be creative. You have the mentality to win games, to play hard, but the first thing is they let us play free. You do your job, but at the same time you can be creative. I played in Germany, too, and in Germany they are really tactical. So if you’re a right back, they don’t want you to go and dribble and score a goal. Your job is to defend in this position. If you get the ball, you pass it to the winger, and the winger goes and be creative. In Brazil, it’s more free. So you have Marcelo, Thiago Silva, Dani Alves — they are defenders but they play free on the field. They pass the ball, they move, they attack, they dribble.

“You have the agents who pay the coach to let the players stay on the team. So this is very difficult in Brazil, because of the politics.”

What role do politics play in football?

I got in Corinthians because one of the staff was my cousin’s uncle. So I was his player. And after one year they took out [the staff] and brought another one, who brought players of their own. So when you’re not one of the best players like Neymar, Willian, like the big names in Brazil, you go with politics. If you know the coach, you’ll be playing. So they put in another decent player in my position, because they make money like this in Brazil.

You have the agents who pay the coach to let the players stay on the team. So this is very difficult in Brazil, because of the politics. I don’t know how it is now, because this was like 15 years ago. But before it was like that. You had the players that were amazing, like three or four players per team. And the rest of the team are agents’ players. So the agents give some money under the table to have their players in there.

How can you be practical as an athlete?

Everybody wants to play professionally. But at the same time, everyone wants to play for a top team because of the money. Everybody wants to do this to change their life.

My whole life, my dream was playing for the national team or playing for the top five leagues in the world. I could not make this. This is still my dream, but as a coach. My new goal is to try to coach a national team or a top team in the world. This will be my challenge.

Looking back, do you think you’d change anything?

Everybody asks me if I regret stopping playing soccer to go to school, because I could make a good team. If I was not married today, I’d say yes. Because I met my wife when I stopped playing soccer. I met her in high school. But when I was in college, I was playing so I didn’t have time. She was my sister-in-law’s best friend. So when I stopped playing, I started going out with my brother. I don’t regret it because of this. And she’s been with me since I was 19 years old. In the end, it’s difficult, but I think it was the best thing to go to school.

Keep up with Bruno’s journey by following him on Instagram.

To contact Christine Kwon, email criskwon2000@gmail.com.