From December 30, 1980 to January 10, 1981, five of the six World Cup-winning countries at the time played in a mini tournament of champions to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the biggest sporting event on the planet. Hosted in Uruguay, the tournament featured current and future stars including Carlo Ancelotti and Diego Maradona — but over 40 years later, El Mundialito has become just a footnote in the game’s vast history book.

Lost to the sands of time is the 1980 World Champions’ Gold Cup, or in South America, mostly Uruguay, known as “El Mundialito.” The concept of the competition was to pit the World Cup champions from the first 50 years of the tournament against each other for bragging rights and the title of ultimate world champion.

El Mundialito was organized by the Uruguayan Soccer Association, known as AUF, with the approval of FIFA to commemorate the World Cup’s landmark anniversary in the country where the first one was held in 1930.

From the start, the odd competition would not have all of the original champions participating, as England, the 1966 winner, did not accept the AUF’s invitation. The country cited a crowded fixture and the reluctance of English teams allowing their players to leave for a month’s time during league play. The Netherlands, two-time runners-up, would fill in, and were joined by Uruguay, Italy, West Germany, Brazil, and Argentina.

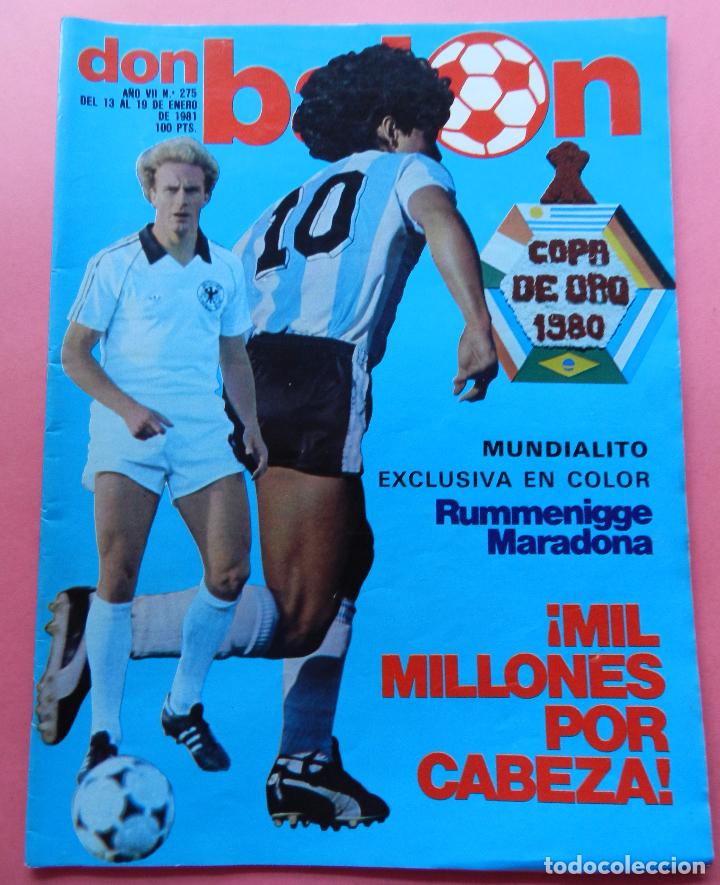

Surprisingly the national teams brought many if not all of their regular players — Daniel Passarella, Ramón Díaz, Mario Kempes, and a kid from Argentinos Juniors, Diego Maradona, were on the Argentine national team. Italy had brought Carlo Ancelotti, Renato Zaccarelli, and Marco Tardelli, Brazil called in Sócrates, Léo Júnior, and Edevaldo, while Germany had brought in Karl-Heinz Rummenigge and Felix Magath. Host Uruguay had virtually their A-team, with greats such as Rubén Paz, Venancio Ramos, Hugo de León, and Rodolfo Rodríguez.

On the field the tournament was largely successful, only played in one venue, the mythical Estadio Centenario. The field was separated into two groups of three — Uruguay, Italy, and the Netherlands were in Group A, and Argentina, Brazil, and West Germany in Group B. The winners of each group would face off in the final.

Shockingly, Uruguay, who had failed to qualify for the 1978 World Cup, ended up first in Group A, with 2-0 defeats over a jet-lagged and disinterested Netherlands side and eventual 1982 World champions Italy. In Group B, both Brazil and Argentina defeated West Germany, and the matchup between the two South American sides ended in a 1-1 draw, with Maradona scoring for Argentina. However, Brazil would go through to the final since they defeated West Germany 4-1, compared to Argentina’s 2-1 victory.

The games were played during the afternoon and night of the Uruguayan summer in temperatures the Europeans were not accustomed to. They eventually wilted under those conditions, as a European team failed to win a match in the tournament.

The final set between Uruguay and Brazil was played in front of over 70,000 fans in Montevideo. Uruguay would defeat Brazil 2-1, and thus the two-time World Cup winners would be crowned Gold Cup champions. The victory, while widely celebrated, would fade with the passage of time and up until recently, it was completely ignored by the rest of the world.

Was “El Mundialito” a Recognized Tournament?

The reports are contradictory. On one side it was not a FIFA tournament like the Confederations Cup, but it was approved to take place by then-FIFA president João Havelange. Many of the top players of the participating national teams made the trip, and as Eduardo Rivas, sports journalist for Canal 4 in Uruguay says, it was organized to the best of the abilities, given the context of those times, by Uruguayan and FIFA officials.

“It was 40 years ago,” Rivas said. “Things are a lot different today than back then, but there was a lot of work to give the tournament exposure. The FIFA press secretary at the time worked very hard along with various members of FIFA. The Centenario was conditioned to play host to the event, with a lot of work done prior. No games were played from September until the tournament began at the stadium.”

Nonetheless, Rivas has pointed out that the tournament has been largely ignored with the passage of time.

“The tournament was put on the back burner over time,” he said. “I won’t say forgotten, but downgraded in its importance. It was played during a difficult context for Uruguay. While it may not have been an organized FIFA tournament it was given its blessing by FIFA.”

Uruguay, which is a nation that has won two Olympic gold medals in soccer, two FIFA World Cups, and 15 Copa Americas, also placed the tournament in a dubious category. According to Rivas, the tournament is largely forgotten even amongst Uruguayan fans, and the AUF doesn’t list the Mundialito alongside its prestigious titles, despite it being a significant victory against marquee football nations.

In What Context Was the Tournament Played In?

When the Mundialito was held in 1980, Uruguay was under a military dictatorship. Since 1973, the country was in control by the civic-military group. While a touchy subject for Uruguayans, during that time the dictatorship arrested more than 5,000 people and the Uruguayan government listed a total of 180 people murdered by the dictatorial regime in 2014.

Ten percent of the population had left the country during those years, and just one month before the tournament, the military government organized a referendum to alter the constitution and try to strengthen their grip of power. The referendum was rejected when 57% of the nation voted against the constitutional changes, and while it took almost five more years for the dictatorship to end, it was the start of change for the small country. The Uruguayan military dictatorship would officially end on March 1, 1985.

The “Legend” of El Mundialito

As time has gone on it was Rivas who brought El Mundialito to the forefront. In January 2022, the journalist, propelled by a mission to find the Mundialito trophy, was able to reunite the cup with the captain of the Uruguayan team, Rodolfo Rodríguez, almost 41 years later.

Rivas laughs as he remembers that at one point someone within the AUF had mentioned that the cup was lost.

“At one point there was an urban legend that the cup was stolen — it was lost, and it was hidden so to speak in the federation,” Rivas said. “I thought I was not going to have success in trying to locate the cup, so I needed a reason to get the cup out in the open and I was able to convince Rodolfo Rodríguez to go in search of the cup and hold it one more time.”

Rivas said that Rodríguez was filled with emotion while holding the cup again, because after hoisting the trophy at the end of the tournament, he never saw it again. Rivas also mentions that the players of that squad feel that the accomplishment of being the top World Champion among World Champions “has been forgotten and is not recognized.”

While played in an era when the world was in the midst of the Cold War and the host country in a military dictatorship, the players of the Uruguayan squad know that the tournament may have been put on the back burner because of the political context in which it was played. Nonetheless, in the case of Uruguay, the team trained heavily for the tournament and defeated the Netherlands, Italy, and Brazil on their way to glory.

For Uruguay, a nation of 3 million people, it is yet another soccer triumph, one of many which have defined the small nation as one of the sport’s most remarkable stories.